Dear Readers, Yours truly has a book in him he will probably never write. But we do have a few chapters in the can, so occasionally, we will share them with you. Below is one such installment, submitted for your approval:

HOW TO BE A RESTAURANT CRITIC

In the beginning there was Lucius Beebe and Duncan Hines. Then came Clementine Paddleford and Craig Claiborne. And finally, there was Seymour Britchky — the man who made restaurant writing entertaining on its own terms.

Before them all (almost two hundred years before them all) there was Mathurin Roze de Chantoiseau. More on the Frenchman later, but of Beebe and Hines and Paddleford and Claiborne it could be said that they took post war America by the hand in the 1950’s and ‘60’s and explained why one should value one eating establishment over another. What Britchky did was something else entirely.

Lucius “Luscious” Beebe was a “macaroni” in every sense of the word. (A “macaroni” being 18th Century slang for a dilettante and a fop.) He was also a frequent contributor to Gourmet Magazine in its infancy and is credited with coining the term “café society.” Another possibly apocryphal quote often had him claiming: “I simply want the best of everything and there’s very little of that left.”

[singlepic=1975,320,240,,]

Lucius “Luscious” Beebe — The food writer as “macaroni”

Beebe was notable for tackling the precious world of fine dining restaurants and wine during the Depression, and unapologetically praising and bashing his subjects according to his whims. His wardrobe was said to contain at least forty suits and two mink-lined overcoats along with numerous pairs of doeskin gloves, top hats and bowlers. Probably one of the last true boulevardiers, he was given the nickname “Luscious Lucius” by none other than Walter Winchell. Among his many writing venues were both Gourmet and Playboy magazines in the fifties, where he devoted articles (they were full of opinion but not straight reviews) of such venerable places as Chasen’s, the 21 Club, The Colony, and The Stork Club.

In his monthly On The Boulevards column for Gourmet, you can read him waxing poetic about the Caesar’s Salads (note the correct and possessive spelling) he encountered in Los Angeles in 1948. And if you want more of his florid prose, then try reading this article on the ten best restaurants in New York City, circa 1946. (Notice there is nary a mention of the chef in any of the places recognized.)

From 1950-1961 he lived in Virginia City, Nevada and revived (and published) the Territorial Enterprise — a newspaper that had once employed Mark Twain. In 1966, Beebe dropped dead of a heart attack at the age of sixty four– on the private railway car he owned — after reportedly consuming an entire bottle of bourbon.

A member of the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame, he is described by on its Web site as having been a “flamboyant gourmet.” Indeed.

A much more middle-brow contemporary of Beebe’s, Duncan Hines self-published his Adventures In Eating in 1936. More pamphlet than periodical, it was basically a collection of pithy notes of inns and local restaurants he had visited in his 30 years criss-crossing America as a traveling salesman.

A typical Hine’s “review” was as terse, spice-free, and to-the-point as a Methodist church supper:

GALLATIN, MO. McDonald Tea Room

6-About 15 mi. N. U.S. 36, Hannibal to St. Joseph, Open all year, 11:30 A.M. to 7:30 P.M. This is a very small town about 70 miles from St. Joe.___29 from Kansas City, around 200 from St. Louis and Omaha, but it is from these and other distant places that hundreds of people come to enjoy their very unusual food. It would require more than one full page of this book to tell you of the many good things to eat prepared by Virginia Rowell McDonald. I am confident you will like your visit here. Let Mrs. McDonald tell you the romance of this place; it is amazing. Whenever I am in this section, I always make a point of going here for dinner. L., $1.50 to $3; D., $1.50 to $3. No liquor.

Duncan Hines-The Mid-American Godfather of restaurant critics

In the days before health inspections and standardization became de rigeur, he and his wife Florence valued cleanliness as much as a well-made meatloaf. But Hines was the real deal when it came to searching out the locally prized and indigenous eateries that defined pre-franchised America. He was the spiritual ancestor of Jane and Michael Stern (of RoadFood and SquareMeals fame), and his Recommended By Duncan Hines seal of approval were a guiding light for those seeking a well-cooked meal in the days before interstate highways defined how we traveled (and ate) by car.

Hines was born and lived out his days in Bowling Green, Kentucky, and was a great connoisseur of country hams. He was also known for placing one order (his) at any restaurant he dined, and then passing the plates among his tablemates. Critics charged that he never went to Europe, and thus had no real basis for judging cuisines and food preparations. But Hines was more devoted to local discoveries and indigenous quality in diners, guest houses and roadside restaurants, than in foreign cuisines that had invaded our shores.

A modest, but by far more far reaching discovery of his was a small roadside restaurant in Corbin, Kentucky that was known for its fried chicken. A popular spot for locals and traveling salesmen alike, that chicken was cooked by a man named Harlan Sanders, who used “Eleven different herbs and spices” in his batter. What Hines first brought to America’s attention became Kentucky Fried Chicken, a franchise that’s done more (or less) for eating out in America than any other restaurant, save McDonald’s. It’s a shame that he is now remembered only for a cake mix.

Just as Hines’s fame began to wane — he died in 1959 — the career of Craig Claiborne was in its ascendancy.

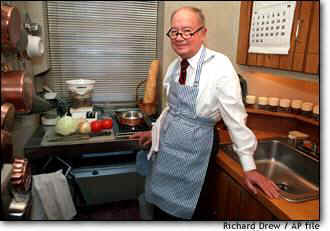

Craig Claiborne — Restaurant critic/cookbook author

As the first male food editor of the New York Times (back then reviews were relegated to the Society Pages), Claiborne inherited a mantle that had long been the domain of society matrons. Claiborne’s only competition in the early 1960’s was Clementine Paddleford, a name that to this day evokes a shudder and grin at the same time. As food editor and restaurant critic for the New York Herald Tribune up until her death in 1967, Paddleford was Claiborne’s chief competition for preeminence among American restaurant writers.

As you can see, there wasn’t exactly a river of testosterone flowing in this state of affairs in the middle of the 20th Century. “Clemmy” as she was known, piloted her own airplane all over the country, and probably out-butched them all.

Clementine Paddleford –– the maiden aunt of American food writers.

Paddleford’s prose was described by Claiborne as being “….so lush it could have been harvested like hay and baled.” To quote from her obituary in the New York Times: “To Clem, and ordinary radish was not just a radish but “a tiny radish of passionate scarlet, tipped modestly in white.” Mushrooms were the “elf of plants,” or “pixie umbrellas.” My personal favorite is from her book How America Eats (Scribners 1960) describing the perfect potable for imbibing at a classic Thanksgiving meal: “Cider is the drink, sweet but edged with a sparkling barm to nip the tongue and wash the palate clean for the next delicious forkload.”

Prose like that would get any modern writer laughed out of any editor’s office…anywhere these days…or maybe not.

Claiborne claims in his autobiography — A Feast Made For Laughter (Holt Rinehart Winston 1983) — that Paddleford “… would not have been able to distinguish skillfully scrambled eggs from a third-rate omelet. I’m not sure that she ever cooked a serious meal in her life.” Ouch.

Claiborne’s first weekly “reviews” began in 1963 and were no more than 50-100 words at first, tucked into the Women’s Section of the New York Times. He never took kindly to the gig (and hated the bestowing of “stars” in his reviews), and left after 13 years to write cookbooks with Pierre Franey and others — including The Chinese Cookbook with Virginia Lee (Harper & Row 1976) — one of the first serious Chinese cookbooks ever published in America.

And then, there was Seymour.

Seymour Britchky was simply, the best. In a class by himself. No one else comes close. The most sardonic, acid-penned, entertaining restaurant writer these shores have seen. (We can’t hold a candle to the critics in England (where restaurant reviewing is treated as blood-sport), but Britchky comes closest to their whip-smart prose.

Should you desire to read a proper eulogy to the man, I refer you to this article by Richard Corliss in Time Magazine, written five years ago, shortly after his death. What drew me to Britchky, and what Corliss captures beautifully, is Seymour’s ability to make reading about restaurants as much fun as being in them.

He wrote the restaurant column for New York Magazine from 1971 to 1991 and over the years published 16 compendiums of his reviews.

Throughout the ’80’s, having Britchky by my bedside was essential reading — constantly fascinating me with tales of The City, and the only restaurants that counted there, in the only restaurant town that counted.

Who knows how I discovered him…probably from picking up a New York magazine in the late 70’s when it was Clay Felker’s counter-cultural, hip and provocative big city glossy — employing some of the soon-to-be-icons of The New Journalism (Tom Wolfe, Gael Greene et al) as its beat reporters and feature writers.

What probably grabbed me first were the droll, high-minded and acid-toned sentences that peppered every review (compared to the New York Time’s washed out, just-the-facts prose), such as: (writing about Fraunces Tavern in lower Manhattan:

Here Washington said goodbye to his officers, (and if he had any sense, to the tavern as well). The successive proprietors of this place have been exploiting that bit of history for decades. The notion of exploiting the taste of good food has apparently never occurred to them.

Or in his review of San Marino-a fancy mid-town, northern Italian:

This long established establishment changed hands a while back. The only visible sign of the transfer of power is the seemingly proprietary new face by whom you are greeted—a lengthy collegiate type in blazer, flannels, garish tie and mountainous hair. He moves around his province with the grace of King Kong in the kitchen. He is doing his schooled best; his hospitality has the stubborn warmth of a robot’s. What a way to make a living, by going through the motions of liking people. He seems to have the connection to the business that a newly prosperous plastic-toy manufacturer and theatrical angel has to his arty off-Broadway production: utter outsider, connected by a cord through which flows only money.

And:

Running a restaurant has little kinship with making great art, but there are similarities. Unless the enterprise is informed by someone’s tastes or preferences or passions or vision, it will fall flat. It may make money, but it won’t leave a mark.

And few who were involved with the restaurant scene in New York in the seventies and eighties will forget his blistering ten-word putdown of the venerable Coach House (where Mario Batali’s Babbo now resides): “Nothing about this place is as remarkable as its reputation.”

He probably wasn’t the nicest guy, loved the racetrack far more than he did writing, and had almost no friends in the restaurant world. When he died (in 2004) only one chef — Andre Soltner — the revered owner of Lutece (with whom Britchky had co-authored a cook book) — showed up at his funeral.

Eight years before, when I attended my first (and last) restaurant writing seminar at the CIA at Greystone, his name and style were brought up by one of the attendees who was as equally infatuated with his prose as I was. The New York Times-types who were on the stage (along with the SAVEUR-types and the Atlantic Monthly-types, i.e. Ruth Reichl, Corby Kummer, Coleman Andrews et al) were quick to dismiss him as a blowhard and a crank, but you could sense the professional jealousy in their voices. None of them had or has the chops to write something as juicy as:

There is a pause at the end of the day’s occupations known as the cocktail hour, and there is a big barroom here to which lots of the guys from upstairs in the Time-Life building repair. They stand around the huge circular counter-height oak tables that bear giant bowls of unshelled peanuts and they light their cigarette lighters, hoist long cold ones and crack peanuts, all without looking. They drop the peanut hulls at their feet, toss the seeds between their teeth and slowly grind them with their huge molars, their jaws rippling. After a while they are ankle-deep in peanut shells, and by seven o’clock this place looks like the elephant house.”

Corliss writes: “He wielded words with a sushi chef’s acuity and vigor. One of the superb prose stylists, his reviews can be read with pleasure and envy by folks who would never set foot in a New York eatery.”

I try to mimic his style occasionally, but my words come out as soggy and dull and ham-handed. For thirty+ years now, I have entertained myself simply by randomly picking a paragraph from a random review, and letting his insights and Sabatier-sharp asides cut to the heart of the matter.

In the eighties I bought a number of his books, but discarded them thoughtlessly. My sole mangled paperback of The Restaurants Of New York: 1978-1979 (Random House) is the only one left. I keep and treasure it by simply peering at it occasionally — never more than one review read at a time — the way a chef would parse the last shavings of a perfect white truffle. I never want to finish reading the words of Seymour Britchky. He was that good.

Really, ELV. Do “we” want some “approval” from the “Readers”? You already have approval (and more) from your sycophants. What more do you want from me?

Why do I have the sneaking suspicion that this book is ready to be published sometime in the future? Was this book project initially your idea? Did someone (perhaps S.S. or A.R.) suggest this to you? Come on, John! Britchky, Alan Richman’s favorite food critic? There’s got to be some behind-the-scenes happenings going on here. Details, please, s’il vous plait, por favor, etc.

And for the record, I not only approve this installment, but I will also give you a box of almond cookies for your very own, when I visit Las Vegas in August.

This has an air of trieste. Has the cancellation of Michelin Guidebook for Las vegas made ELV a little maudlin?

John

Can you tell me how I can reach you today (monday, june 29)? I’m looking for a Las Vegas restaurant expert for an article I’m writing. Pls email direct.

Cheers

Lisa Jennings

Nation’s Restaurant News

Los Angeles

Great stuff! That is all…

I, for one, will be standing in line at your book signing.

Whether ELV has scribbled notes with a number two pencil and kept the papers stashed away to resurrect someday–or, as some have suggested, he’s got the book in the can already–it doesn’t really matter now does it?

What’s important here is that ELV has given us a glimpse of a very important chapter in the history of food writing, and if the succeeding chapters of “the book” are as captivating as the musings on Paddleford, Claiborne and Beebe, we will be in for a delicious tome.

I’m proud of ELV for telling the tales of these monumental figures in the history of food writing. Far too many people call themselves “food writers” today without nary a whit of the contributions of the forebears of the craft.

As ELV has done, we should all take the time to learn about these Masters of the art of food writing as it can only serve to elevate our own writings to somewhere close to their level.

Perhaps the best way to show our appreciation is to begin a biography of Mr. ELV himself — a sort of pre-memorial, as it were. A picture book of all the links to the staff of ELV would be a good start.

Someone asked me if I said this about Seymour and–no! Impossible that I could ever dismiss him. I also treasured my battered copy of his collected reviews, in the old (ie original) New York Magazine typeface, and wrote him a fan letter in college, and had the pleasure of meeting him on numerous occasions, and actually got to edit him (on a jazz piano bar) at my first job. He was certainly singular, and worth both remembering and reading.