Having been to Paris a dozen times in the past twenty years, I pretty much consider myself an expert on the subject — which puts me firmly in the camp of roughly a million other Americans who, at the drop of a beret, will tell you everything you need to know about how they enjoyed themselves over there.

But like anyone who vacations to the same spot again and again, one starts to feel a certain knowingness and possessiveness — a visceral connection to claim it as your own. But let’s not fool ourselves, I may be an accomplished tourist– familiar with Paris’s streets and sites, and able to orient myself quickly — but I’m simply an enthusiastic visitor. With the Olympics coming up this week, and Paris! Paris! Paris! being all over the news, the least I can do for my loyal readers, is offer a few travel tips should you find yourself headed there anytime soon, either physically or in your dreams.

We’ll start with some general advice, and sprinkle in some words of wisdom, heavily sauced with sarcasm…and a buttery Béarnaise, of course.

First, let’s concentrate on the important things.

Getting there: Take Drugs! Get sleep! We’re talking on the airplane, silly. Benadryl works for me. Gummies for others. Steal your mother’s Valium if you have to, but knock yourself out for at least 4-5 hours of the flight.

You will arrive in the early morning. The airport, even at 8:00 am, will be a mess. Charles DeGaulle is either the biggest headache in travel (worse for departing flights than arriving), or just hugely annoying on par with dozens of other international hubs. It is never a pleasant experience so grit your teeth, get through it, and think of the meals ahead.

Clear passport control, get your bags, and find a cab. Parisian taxis are good and reliable and won’t try to cheat you; but Uber is better. It’s easier to find the cab stand at the arrival terminals than the rideshare pickup areas so hop in and show your hotel’s address to your driver on your phone. Once in town, stick with Uber.

The ride from the airport to the central arrondissments can take anywhere from 30-90 minutes to go 34 kilometers (21 miles) depending on traffic. The only time it’s ever taken me less than an hour was at 5:00 am, on a weekend, in a driving rainstorm.

Don’t even think about going in the summer. The third time I went to France was in late June, 1998 and it was sweltering, crowded and miserable. And it’s only gotten worse the last quarter century. After two weeks of sweating through crowds and a dozen shirts, I vowed then never to return unless it was sweater weather, and I’ve kept that promise for 26 years. The good news is Paris is more north than people realize (roughly on the same latitude as Rolla, North Dakota(?), and late May is a gorgeous (and quite cool) time to go.

Once you do get there, say, this fall or when the Olympic dust dies down, here is how I attack la capitale de la gastronomie:

Bring your best thick-soled walking shoes. Better yet, bring two pairs and don’t worry about being fashionable. Nothing brands you a tourist faster than showing off your shiny spats (or spiked heels) when all the locals are tromping about in clunky boots.

Speaking of fashion: scarves are to les hommes de Paris what feathers are to a peacock. As soon as the temperature dips an inch below 70, they wrap their necks in them as if they were trekking through Greenland. Bring one (preferably the size of a bedspread), or buy one there and wear it like a world weary Parisian in love with his blanket.

Final dress code note: Paris is a lot less formal than it used to be. However, in some of the tonier hotels and gastronomic cathedrals, without a sport coat on, you will feel as out of place as a Twinkie in a patisserie. So men: bring a blazer. Women: you’re on your own. These days you can get away with almost anything.

As for accommodations…

Decent hotels are everywhere. Paris is full of great small hotels with clean facilities and helpful staffs. Like everything else, prices seemed to have risen 50% in the past five years. Expect to pay at least $250/night for a decent bed in a smallish room, with plumbing that’s a lot more reliable than it was in 1994.

It may be a bit off-brand, but for twenty years, I was the king of the shitty Parisian hotel — Hotel Malte, Hotel Crayon Rouge, Hotel Therese, Hotel Cambon, Hotel Select, Hotel La Perle — from a Best Western near the Louvre to a hot sheet joint around Brasserie Flo in the Tenth that I used for a one-night stand {food, not sex} — were, for years, where I parked my solo self before trekking to a three hour lunch or four hour dinner.

Then, marriage civilized me. Like most wives, The Food Gal® has more refined sensibilities when it comes to these things, and doesn’t appreciate the charms of tissue-thin linens, pillows the density of cotton balls, and showers the width of a golf bag. For her I bite the bullet and try to book Le Relais Saint-Germain (in the heart of the Left Bank), or Grand Hôtel du Palais Royal (a block from the Louvre and Palais Royal) so she doesn’t have to walk over the bed to use the bathroom.

Regardless of where you cool your heels, it’ll be late morning when you arrive in town and your room will not be ready. This means you’re going to have a few hours to kill before you can wash off the airplane grime — which is why sleeping on the transatlantic flight is so important.

Another travel hack I’m fond of is a bit harder to cultivate, but it comes in particularly handy when you have to wait hours for your room:

(Towels so fluffy they barely fit in my suitcase)

(Towels so fluffy they barely fit in my suitcase)

Have rich friends! The kind who, in the before times, would’ve been bossing around porters with Goyard streamer trunks strapped to their backs. If you’re fortunate enough to befriend someone in the carriage trade, they might let you hang out at The Ritz (above), Hotel Lutetia, Mandarin Oriental or Cheval Blanc (where the $2,000/night rooms are always ready) before you crawl back to your hovel to begin a week of listening to other people flush their toilets.

Wherever you are, you’ll be dead tired (it’s the middle of the night your time), and in need of a shower. And, if you haven’t read this blog, you’ll find yourself standing in the middle of some hotel lobby, smelling like dried sweat and musty airplane cabin, and wondering what to do until 3:00 pm. This is where planning comes in. This is why leaving meals to chance, especially in a target-rich environment like Paris, is dumber than ordering a cheeseburger on the Champs-Elysee.

Book a lunch venue for the day you arrive at a nice cafe/bistro within a few blocks of your hotel. Decent bistros are more common in Paris than baguettes these days, and with a little research, you can find a foodie favorite. Consult Paris by Mouth if you want to be in-the-know and au courant, and reserve a week or so before you arrive, knowing that your first meal on French soil will probably leave your waiter wondering whether it is you or the aged Espoisses he’s sniffing.

Here’s a sampling of places which barely scratches the surface of all the cornucopia of dining choices which await you, sort of in alphabetical order:

Chez L’Ami Louis The link is to one of (the famously dyspeptic) A. A. Gill’s most acerbic reviews in which he savaged the place. Enjoy his prose, but ignore his vitriol. He must’ve been feeling more splenetic than usual, because L’Ami Louis is famous for a reason(s), and the reasons are it has some of the best poulet, foie gras, a haystack of frites the size of your head (above), and baba au rhum in France. The hardest thing about it is securing a reservation. (Use a concierge.) The staff is gruff, but actually quite nice.

You could build a two week vacay around eating in only these and not have a bad bite. But there are bigger fish to fry in Gay Paree (see below).

As you can see, I lean heavily classic when it comes to French food — from cuisine bourgeoise to haute. If you want trendy (lots of tweezers, Franco-Sino mashups, high-wattage outposts from some enfant terrible) you’ve come to the wrong place. And If you’re looking for cheap eats, you’re really at the wrong address. That said, the street food of Paris is quite the bargain, and worth checking out.

Begin with a Day One lunch and you’ll start your visit with a thorough immersion in French food culture before you’ve even had a chance to unpack your bags.

After lunch (With a mandatory carafe of wine? Bien sur!) you’ll be more tired than Gerard Depardieu walking up a flight of stairs, but resist mightily the urge sleep. Stagger back to your hotel, and retrieve your bags from the lobby, check in, shower and change, and then….do anything but fall asleep. You’re full, you’re exhausted, and nothing sounds better than hitting the rack….but it’s only 5 in the afternoon. Collapse then and you’ll wake up at 2 am, rarin’ to go with nothing to do, Dozing off on your first day is a serious rookie mistake and will consign you to days of waking up in the wee hours and conking out in mid-afternoon, which will rob you of days of eating enjoyment.

This is where French café culture comes in to save the day. We guarantee that there will be a cozy one within a stone’s throw of your hotel. Find it, plop yourself in a chair, order a café crême, double espresso, or café allongé, and caffeinate yourself to the nines. Take your time. Play on your phone. Read a book. They don’t care if you’re there five minutes or five hours. Once the jitters set in, that’s your sign you can make it a few more hours until a respectable bedtime.

Walk your ass off – our second favorite pursuit in the City of Light, and the reason we actually drop a pound or two on every trip. Pick a different neighborhood every day and then start walking. It almost doesn’t matter in what direction — (almost) everything there is to see in Paris is within a four mile radius of the Louvre, and picturesque strolls are everywhere. A few of our favorites. St. Honore du Faubourg (shopping!), Rue de Montorgueil (food), Rue Caulaincourt (gorgeous neighborhood in Montmartre), Rue de la Roquette (Bastille delights), Rue des Martyrs, Rue Rambuteau (cafés galore), Rue des Franc Bourgeois, or the entirety of Saint Germain de Prés, you get the picture.

“The best of America drifts to Paris. The American in Paris is the best American.” – F. Scott Fitzgerald

Have a drink at Harry’s New York Bar. All Americans do. It’s nothing to be ashamed of. Then leave cocktails to the sheeple waiting at Bar Hemingway at the Ritz. As good as the drinks are at both of them, you’re here for the food and wine, pilgrim, not to booze it up. Getting drunk on vacation is for this side of the pond. And Germans.

Adopt a wine bar.

Better yet, explore two or three. Wine is as much a part of French culture as sugar water is to ours. Going to Paris and not drinking wine is like touring Italy and skipping the pasta. You won’t find better French wine anywhere in the world, or at better prices. Here’s few of our faves:

Most likely you’ll still be full from lunch, so plan on a tipple and light bite at one of these (all of them offer snacks to full meals), and then head to your home base to hit the hay. Don’t ask me to recommend natural wine bars though. We have nothing in common if you enjoy imbibing alcoholic kombucha dappled with scents of mouse droppings and hints of musty closets and sweaty feet.

Get the museums out of the way. My wife had been to Paris three times before she stepped inside the Louvre. Every time we’d walked past it she’d whine, “I want to see the Louvre.” To which I always replied, “There it is, now you’ve seen it. Let’s go to lunch.”

Pro tip: Hit the Louvre early on day two so you won’t have to put up with such misguided caterwauling. You’ll still be getting your sea legs, so schedule a private or group tour as early in the day as you can. We’ve had wonderful luck through Viator, and when you sign up for the small group tour, often it’s just you and the guide. Don’t forget to tip the guide (about 20 euros/pp is appropriate, more if they spend extra time with you, as ours did.) If you’ve got the energy, cross the Seine and knock out the Musée d’Orsay in the afternoon. Dispose with those and you can forever pat yourself on the back for being more cultured than the slack-jawed rubes you call friends back home.

The French are the biggest oyster and cheese eaters in the world. Paris is the apotheosis of shellfish appreciation, and glories in its fermented curd culture, so take full advantage.

Skip the Eiffel Tour. It’s a total shitshow these days. You wanna see La Tour Eiffel? Look up from anywhere in Paris and you’ve seen it. Ditto Notre Dame. The approaches to both are crammed with screaming toddlers, obnoxious Instagrammers, and hordes of tour groups speaking everything from Cantonese to Swahili.

Do not miss a river cruise. This should be mandatory for first-time visitors. We did a lunch cruise a year ago and the food was remarkably tasty, as were the house wines. The dusk and evening cruises are supposed to be spectacular. Whenever you go, it will be three of the best hours you’ll spend in the city.

Restaurants! Restaurants! Restaurants! Remember, Paris isn’t just the ancestral home of the restaurant, it is also the food capital of the world with at least 44,000 restaurants (cf. New York City, which has four times the population and half as many food outlets). Equally impressive is the fact that most of its temples of gastronomy are open for lunch — and the food is just as good, the portions a little smaller, and the tariff a bit shallower. Plus, you have the added bonus of being able to spend the rest of the day walking it off.

This territory has been covered extensively on this blog before. To summarize, consider your options:

Guy Savoy might be the best restaurant in the world.

L’Ambroisie is the pinnacle of classic cuisine in an historic setting, and even though the menu is entirely in French, they are extraordinarily friendly and patient with clueless Americans.

Taillevent might be the swankiest place on earth to have lunch. If you don’t want to spring for such an upscale extravaganza, Taillevent’s wine-centric spinoff — Les 110 de Taillevent — comes highly recommended by our staff:

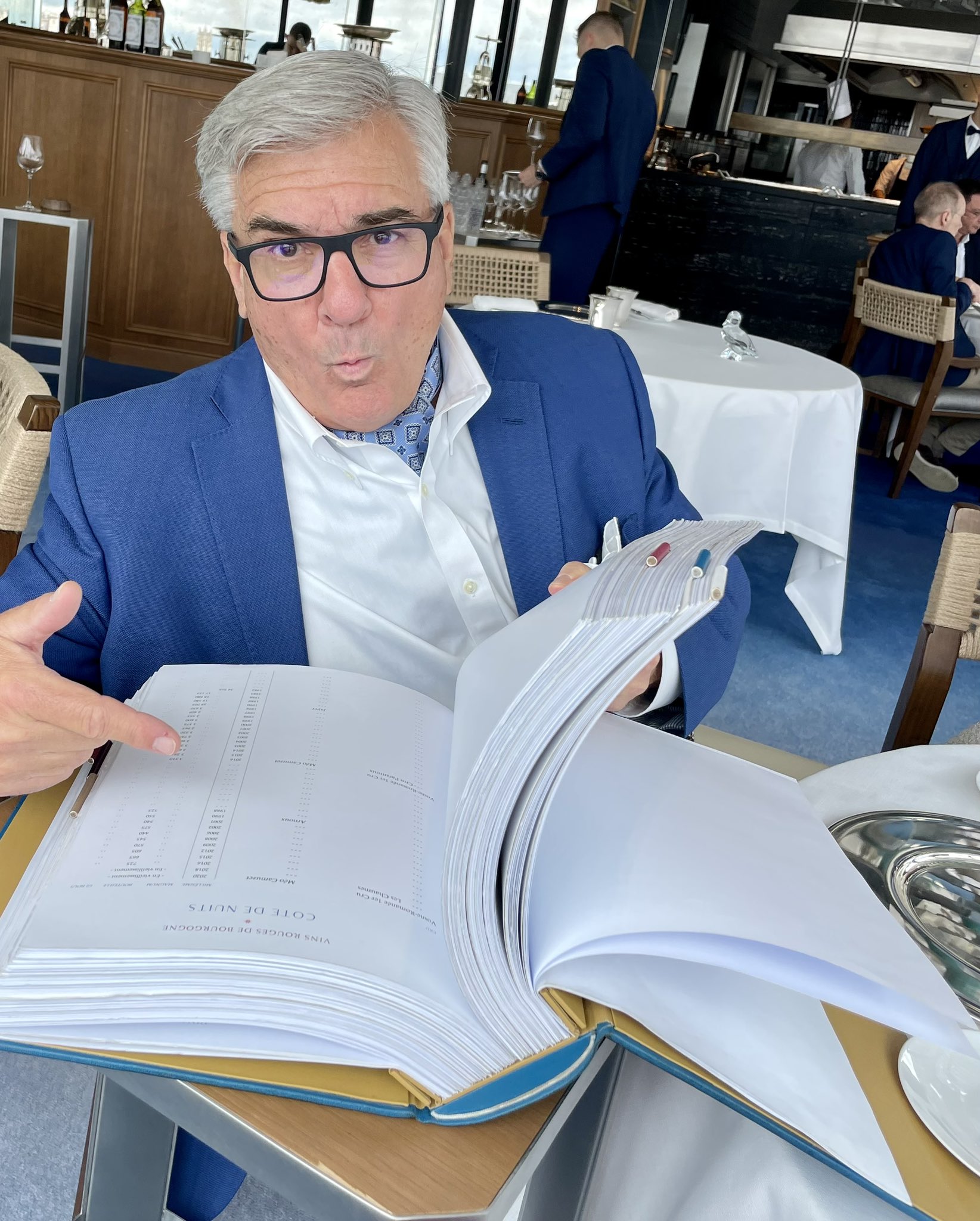

The legendary La Tour D’Argent may be the most spectacular combination of food, wine and setting on the planet. The wine list alone is worth a trip:

Pro Tip: Do not despair. Trying to navigate this tome is more futile than trying to parse French genders. Do what the pros do: Ask for it respectfully; accept it religiously; peruse it solemnly; then point to a region and a price point and throw yourself on the mercy of the sommelier. In multiple visits they have never steered me wrong.

Pierre Gagnaire continues to be one of gastronomy’s most inventive chefs. He’s may be in his 70s, but his restaurants haven’t lost their fastball. Gaya — his cozy seafood refuge, tucked into a Left Bank neighborhood — remains a stunner, toggling between tradition (impeccable Dover sole, below) and innovative takes on things that swim:

Another eye-popper is the over-the-top Le Clarence — ensconced among the sconces in a re-tooled 19th Century Golden Triangle mansion. Renowned for its elegant cuisine, Chateau Haut-Brion collection and chariot de fromages, this joint is so fancy, you can be excused for thinking the staff is looking at you as if you have a bone in your nose or a papoose strapped to your back.

Arpège retains its 3-star status, with many glorifying its exaltation of turnips, lettuce and the like. Others claim it is past its prime. We are firmly in the latter camp.

Le Climats — a perennial favorite for our annual Burgundian bacchanalia — has closed, and Le Grand Vefour (a must-stop for 27 years) seems to have shed its Michelin history and re-made itself into a glorified bistro. Pity.

If we were to chase les trois etoiles again, it would be at Alléno Paris au Pavillon Ledoyen or Le Prés Catelan. Or Lasserre. We’ve never been, but it’s on our short list. Maybe some day we’ll get there, to Lasserre. In the meantime though, we’ll mostly leave these temples of excess to the nouveau riche gastronauts who frequent them.

You will enjoy yourself much more, and save a little coin, by sticking with lunch at a Michelin 1 or 2-star — where everything is almost as perfect, and what little isn’t is only known to those inspecting the place with a microscope.

Pro tip: Lunch is the right move. After a morning of cultural enrichment, museum fatigue, shopping, or some other waste of time, a proper dejeuner on day two is perfect for your first big deal meal. This is when the big game hunting begins in earnest. Do you want to see what’s new on the gastronomy scene? Visit an old reliable? Surround yourself with luxury? Or try something edgy and out there? It’s time to step up your game and take the Michelin plunge in the last place on earth where the stars actually mean something.

And don’t leave without at least one meal at Le Train Bleu – still the most visually spectacular restaurant in the world. Be forewarned however, cheap travel and Instagram have turned what was once a beautiful sleeper (attended to solely by lovers of Belle Epoque decor and those waiting for a train at Gare de Lyon) have made it a favorite of the selfie-stick set. It’s probably a tad more breathtaking at night, but tables are easier to come by at lunch. The food is remarkably good for such a large operation. So is the service.

For those not wanting to spend a car or house payment on a meal: most sidewalk cafés have perfectly serviceable set menus (always a fixed price for three courses) which will keep you alive. And don’t underestimate the gastronomic joys of le jambon-beurre or a Breton galette (basically a buckwheat crêpe) — both of which are easily found on the street, food stores or in the boulangeries which dot the city.

Spend a day in Montmartre. But make it a weekday. Weekends are more crowded than Disneyland on the Fourth of July. Go early, grab a kouign-amann at Le Pain Retrouvé (above) to fuel your quads as you traverse the steep streets:

One full day won’t be enough but it will give you a nice taste of life in the village where Amélie roamed, and one which Toulouse-Lautrec might still recognize. For lunch: duck into Le Coq et Fils – Antoine Westermann’s ode to poultry. It’ll be the best $150 you ever spend on a yardbird:

Hit a farmers market. This is recommended even if you’re not in Paris solely to eat and explore the food scene. (Quelle horreur!) The sheer variety of seafood, vegetables, cheese, prepared foods and meats puts eating in America to shame. Since you’re a tourist, you mostly will be gawking instead of buying stuff, so set aside an hour or so to gawk to your heart’s content. The vendors tend to be way friendlier than they used to be.

Visit Père-Lachaise — only if you feel a kindred spirit with Oscar Wilde or Jim Morrison. Otherwise, skip it. The neighborhood is way out of the way, with little to offer but seedy streets until you get closer to Place de la République or the Marais. Plus, it’s full of dead people. Lots and lots of dead people. Underneath mountains of concrete. It’s a Catholic thing.

Cultivate a French Connection.We have a friend. Let’s call her Babette. We can’t claim Babette as our own since we met her through close friends, but now she’s part of the family. She’s Parisian, successful, insouciant, funny, thin, beautiful — one of those gals who falls out of bed looking like she just stepped out of Chanel — and always there to guide us to a hot spot, or help secure a reservation. She also has the worst taste in men since Britney Spears. There have been so many Jacques, Gilles, Françoises and Hervés we can’t keep them straight. Most of them look like they came straight from Central Casting, or were runner-ups in a Jean-Paul Belmondo lookalike contest. Whatever. This steady parade of suitors somehow makes Babette even more charming. It’s all so very very French, right down to the cigarettes, nonchalant melodrama, and scarves the size of bed spreads wrapped around everyone’s necks:

Don’t bother learning the language. My travails with the French mother tongue go back half a century. After failing to learn it at least a dozen times, I’m now simply grateful for Google translate, and for the two generations of Frenchmen who have grown up learning English in school. I’m looking forward to my teenage grandson becoming fluent, ready to serve as my translator and squire me around France in my golden years, as long as I’m paying for everything.

Les Invalides is a must — especially for history and military buffs. Perhaps I’m remembering my visit(s) through a rose-tinted haze, but I seem to recall The Food Gal® being riveted by the intricacies of the French 75 field gun, and questioning whether Napoleon was premature in releasing Marshal Ney’s cavalry at Waterloo.

Pretend you’re a Frenchman — which is best done by exploring every inch of the Luxembourg Gardens and the Jardin des Tuileries. Pack a lunch, grab a seat, and watch the world walk by. There are no two more romantic parks anywhere in the world. It’s only about a 30 minute saunter between them, so set aside a day for urban hiking, provision yourself at Marché Maubert or Marché Saint-Germain and go nuts.

Hotel bathrooms are your friend. The one downside of walking for hours on end (and finding yourself miles from your hotel) is you are always keenly aware of your bladder’s capacity. While small cafes and restaurants frown on you popping in just to empty your vesica urinara, larger hotels always have facilities on the first floor, and generally don’t mind if you use them (as long as you are dressed like you could be a guest). I’ve been told public toilets dot the sidewalks all over Paris, but my chances of using them are roughly the same as the Louvre being turned into a Wal-mart.

Eat (and drink) in Montparnasse. Just the way Hemingway and James Joyce did. The cafes – La Coupole, La Closerie des Lilas, Le Dôme, La Rotonde, Le Select — are legendary. The seafood is impeccable, and the atmosphere straight out of the Roaring 20s. These are the joints that literally created the term “café society”, and each is an eyeful, generally welcoming, with copious indoor and outdoor seating. This makes them especially attractive for those who haven’t booked in advance. Being a bit removed from the tourist corridor also means you’ll be rubbing knees more likely with locals than cargo shorts. A visit to at least one should be on every foodie’s itinerary.

(Toilet paper and big screen TVs on Aisle 4)

(Toilet paper and big screen TVs on Aisle 4)

Shop the way human beings were meant to: in department stores. Department stores in America are an endangered species, but Galeries Lafayette (above), Le Bon Marché, Printemps, BHV, La Samaritaine— are shrines to civilized shopping and still going strong in the City of Light. Most are architectural gems in their own right, and whether you’re buying or browsing, it is time well-spent. Added bonus: most have restaurants/food halls/gourmet grocery stores associated with them which are a treat unto themselves, and a perfect place to plan a picnic.

Make a pilgrimage to Poilâne. It’s roughly the size of my closet, and many Parisians scoff at its international success, but this is where it all started — the shop that made the world fall in love again with French bread.

“Paris is a place where, for me, just walking down a street that I’ve never been down before is like going to a movie…Just wandering the city is entertainment.” – Wes Anderson

What have I missed? Strolling the Seine. Poking around the Jardin du Palais-Royal. Soaking up the history of the Place de Vosges. Croissant hunting (this award-winning knockout is from La Maison d’Isabelle):

Copper cookware browsing at the iconic E. Dehillerin. Haute couture. Immersing yourself in the cacophony of the Marais. Exploring the Trocadero, Champs-Elysee, Bois de Boulogne . The Opera House (Palais Garnier), Catacombs, Arc de Triomphe (another shitshow, but give it a whirl), Musée Cluny, the Sorbonne, the Latin Quarter, Pantheon, and a dozen other museums. (One of these days, we’ll get to Musée Carnavalet, the museum of the City of Paris.) It’s all there for the taking, or you can simply stroll around for days, snapping jaw-dropping pictures until your thumbs get tired.

Hemingway called Paris a moveable feast and truer words have never been written. But it is much more than just the best food city on earth. Paris my way will always be the greatest banquet in the world for the intellect, the senses and the soul.

Take us home, Edith:

(Grumpy gastronome grades great and egregious grub)

(Grumpy gastronome grades great and egregious grub)

(Murderer’s Row)

(Murderer’s Row)

(A Fine place to pig out)

(A Fine place to pig out) (Olé, José!)

(Olé, José!) (“The test of a chef is roast chicken.” – James Beard)

(“The test of a chef is roast chicken.” – James Beard)

(Be-ewe-ti-ful)

(Be-ewe-ti-ful)

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-pmn.s3.amazonaws.com/public/6UM7RTBJTRBLDCC46VIS35M4FI.jpg)

(Thai roast duck at Lamoon)

(Thai roast duck at Lamoon)

(Francophiles)

(Francophiles)

(Chicken in Seine)

(Chicken in Seine) (Chip off the old Bordeaux)

(Chip off the old Bordeaux)

(Truffles in paradise)

(Truffles in paradise) (An urchin to satisfy)

(An urchin to satisfy) (Egg-cellent)

(Egg-cellent)

(Mary had a littlest lamb)

(Mary had a littlest lamb) (Praise cheeses!)

(Praise cheeses!)

(Who gets the pepperoni?)

(Who gets the pepperoni?) (Waiter, what’s this fly doing in my soup? The backstroke, sir.)

(Waiter, what’s this fly doing in my soup? The backstroke, sir.) (Inkcredible)

(Inkcredible) (Here’s a tip: eat more greens)

(Here’s a tip: eat more greens)

(I kidney not, you mustard try these)

(I kidney not, you mustard try these)

(It doesn’t get any cheddar than this)

(It doesn’t get any cheddar than this)

(Toto, we’re not in Taco Bell anymore)

(Toto, we’re not in Taco Bell anymore)

(Work. Work. Work.)

(Work. Work. Work.)