Quality is always inversely proportional to quantity. – Lionel Pôilane

There are passion restaurants and there are money restaurants.

Passion restaurants are imbued with a feeling — a personal connection between staff and client — which is palpable. The people behind them are to the kitchen born, and can’t imagine themselves doing anything else.

Restaurants in it solely for the shekels betray themselves with a vibe (sometimes subtle, sometimes not so) which says, “you’re just a number to us.”

Ferraro’s is a passion restaurant; Raku is a passion restaurant; Tao is a money restaurant. Esther’s Kitchen began as a passion project but is now about to morph into the Denver Mint.

To be “The Best Restaurant in Las Vegas” you have to treat cooking as a religion, not a job. To be the best at anything, you have to be driven by something other than profit. When you think about things that way, the field gets very narrow, very quickly.

Before you jump down my throat faster than slippery bivalve, no one has to remind me that all taste is subjective and “the best” of anything is a concept more nebulous than a Donald Trump stump speech.

My idea of what makes a restaurant “the best” are probably far different from yours. By “the best”, I mean an eatery of quintessential excellence, which brings a spiritual intensity and machine-like consistency to the table. Decor means little or nothing to me; service is important, but not primary; and the dazzle factor must all be on the plate.

Your idea of the best in town might be a plush, no expense spared beef emporium, dripping with umami and testosterone. Or it could be an elegant Italian, smooth as Gucci leather, where they always know your name and the pasta is nonpareil. Perhaps you put a greater emphasis on intensive care service, or cartwheels in the kitchen. Some of us seek adventure in eating; others crave familiarity. But there are standards, and we at ELV are here to uphold them.

So, for purposes of this discussion, these are the essentials…

Things it must be:

Singular, i.e., not part of a chain, a group or empire

Chef-driven

Food-focused

Made-from-scratch-centric

Quiet

Comfortable

Seasonal

Small

Serious (but not too)

Things it must not be:

Too big

Too popular

Too corporate

Too commercial

Too many recipes

Too many clowns – as customers or in the kitchen

Filled with men showing off or women whooping it up – but I repeat myself

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

Which brings us to a sliver of a space, impossible to see from the street, tucked into an obscure corner of Chinatown. It sits behind a tire shop and to the left of an obscure Persian restaurant. If you don’t know what you’re looking for, you can be standing right in front of it and not know you’re mere feet away from a gastronomic trip to Japan –without the language barrier or a 13 hour plane flight.

Beyond the noren, the front door at Kaiseki Yuzu leads you into a dark, narrow hallway, decorated in spare, Japanese style, leading to the 30 seat kaiseki restaurant at its end. To your left (inches from the threshold) is a curtain leading to those six seats (above) and the most personally-crafted meal you can have in Las Vegas.

What chef-owner Kaoru Azeuchi (pictured at top of page) and his wife Mayumi have done since moving into this shoebox four years ago is remarkable. Not only have they garnered a James Beard Finalist nomination, but they have raised the bar for Japanese food in Las Vegas in a manner not seen since Mitsuo Endo opened Raku back in 2008.

(Soy good you’ll be wasabi yourself)

(Soy good you’ll be wasabi yourself)

The kaiseki menu (above) — hyper-seasonal and glorious in its own right — is the main point of the restaurant. For the uninitiated, kaiseki is a very particular form of Japanese prix fixe dining (originally for the nobility), centered on precious ingredients, sourced at the peak of flavor, and fashioned into minimalist, edible art. Kazeuchi is a master of the craft, using the food chain (from the humblest of vegetables to the most exotic beef) to provide him a palette from which he creates masterpieces both visual and edible. If more beautiful food exists in Las Vegas, we haven’t found it.

The sushi bar at Kaiseki Yuzu wows you in a different way. The menu is the same price ($165/pp) as the $165 Chiku kaiseki, with fewer proteins than or the more luxurious Shou ($210) set. The emphasis at the bar is on Osaka-style sushi and pristine fish — an omakase experience where you sit back and enjoy the ride, because each of the ten or so dishes placed before you will concentrate your senses on the sublime expression of each ingredient.

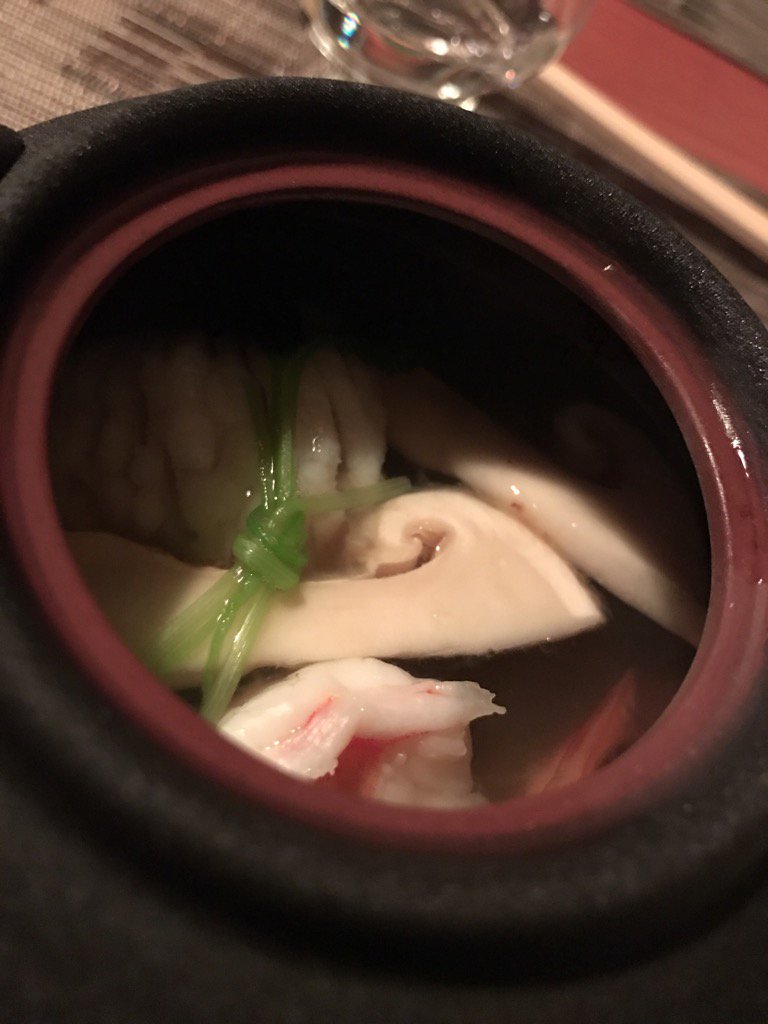

Chef John Mau (above) — a Michael Mina veteran — has commanded the sushi space since it opened last August. With a helpful assistant at his side (shout-out to Olivia!) he slices, dices, and explains everything from the five Zensai bites which start your meal to that impeccably chosen sushi to the Kanburi (yellowtail) in a hypnotic shabu-shabu broth, whose crystalline appearance belies its potency.

Deceptively simple is a phrase often used to describe Japanese cuisine — where much more is always going on than meets the eye. So it is here with everything from the translucent rice to the immaculate fish. Even something as prosaic as a spicy tuna handroll is given new definition by being chopped before you, and barely folded into napkins of nori — echoing the sea in all its vegetal, sweet and saline glory.

Having a chef in such close proximity, in the presence of such unsullied seafood, makes this a personal experience unlike any other in town. The windowless room (very Japanese that) wraps you like a warm hug, and the gestalt of all three combines to make you do one thing: think about sushi like you’ve never considered it before. Every nuance is heightened; every bite attains a higher purpose — a commiseration between the animals which sustain us and the humans who enhance their taste. All done while making food delicious enough to send a happy shudder up my spine.

There is an intimacy born of a great Japanese dining experience which the West rarely approaches. It is born out of trust and respect between chef and customer. You are placing yourself in their hands (literally), and both sides recognize a bond created by what the chef will hand-craft to please, enlighten, and nourish you. The rawness of the cuisine, and its insistence upon absolute freshness, coupled with the hand-molding of almost every course demands this level of faith.

Japanese chefs make food taste most like itself, all while making it appetizing and beautiful. There is a distillation to the essence of things which informs their cuisine. There is no place to hide in a Japanese meal. If you give yourself over to it, you start appreciating why French chefs in the latter part of the last century flocked to Japan. It wasn’t only because the Japanese were micro-plating food decades before any Frenchman had heard of tweezering micro-greens. It was because this is high amplitude restaurant food in its purest expression. Kaiseki Yuzu is the closest thing we have to a trip to the Land of the Rising Sun, and it is right on our doorstep. There is no more unique, delightful, or passionate restaurant anywhere in Las Vegas.

(

(

(Not included: lubricant)

(Not included: lubricant)

(Sand dabs by the sand)

(Sand dabs by the sand) (Niki knows kaiseki)

(Niki knows kaiseki)

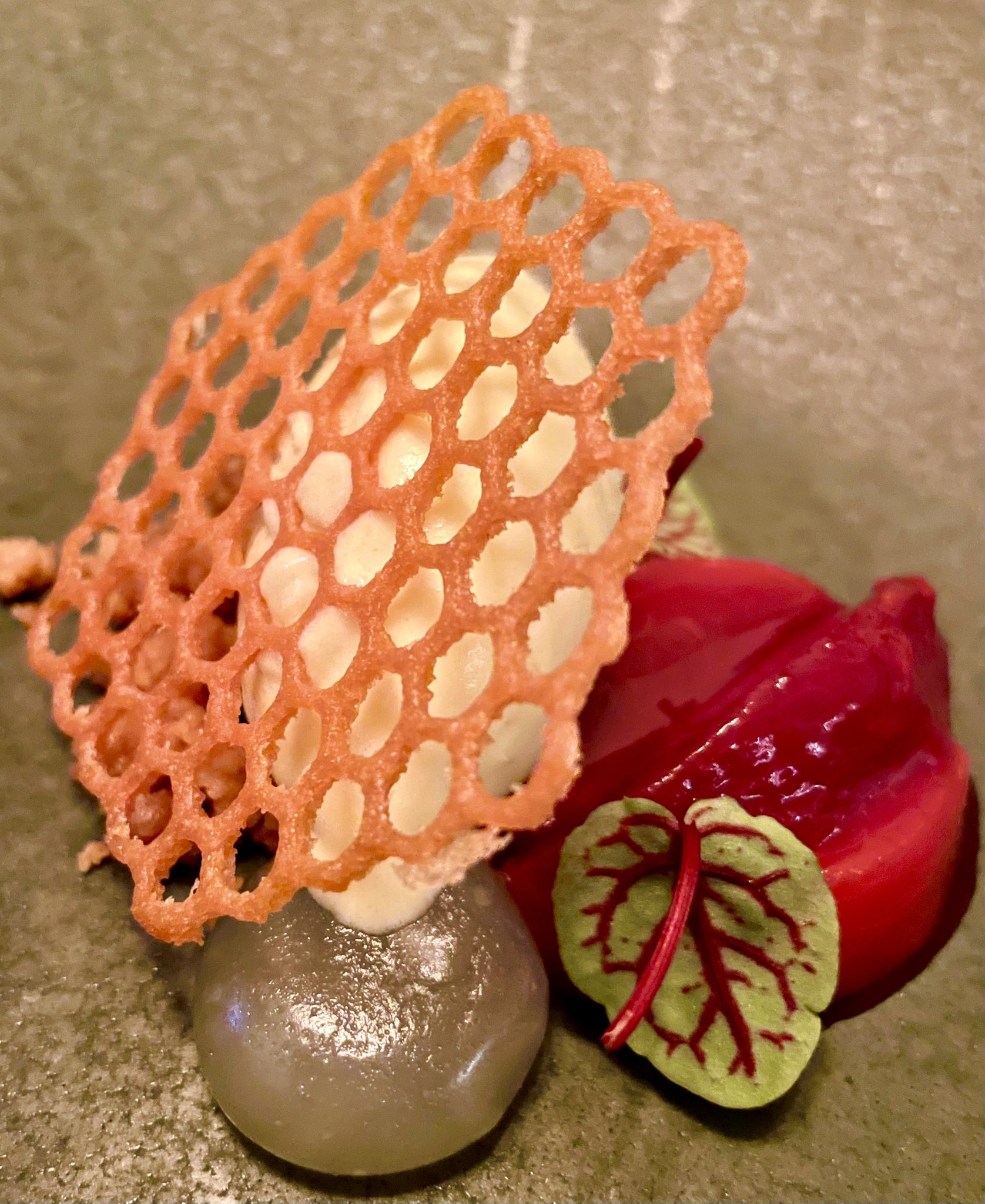

(Mizumono – ginger-poached plum, lavender ice cream, warabi mochi)

(Mizumono – ginger-poached plum, lavender ice cream, warabi mochi)