The trouble with Paris is the human body is only designed to eat 4-to-5 meals a day.

Such is the conundrum we face daily as we ramble down its rues, and contemplate the cornucopia before us.

Spring is the perfect time to provoke the appetite for this moveable feast. The air is crisp but not cold. It may rain a little but there is revival in the air, and spring in everyone’s step. Sun worshipers flock to the public gardens and you can literally feel the city stirring itself from months of slumber. April is too late for somber bleakness to blanket the city in its wintry cloak, and too early for tourists to harsh your mellow. You can dress up (or down) without fear of ruining your clothes through sleet or sweat, and walk all day without rising temperatures stealing your stamina.

Other than October, April is the ideal month to eat your way through Paris.

So gird your loins and crack a bottle of your favorite fermented French libation, for here is another love letter to the City of Light, and why springtime is the best time to pursue its pleasures of the palate.

HIT THE GROUND EATING

It was around my third bite of a tangy tartare de boeuf at Ma Bourgogne — one of my favorite bistros in Paris — that I realized one of my dreams had come true: despite my pitiful failure to master all but the most rudimentary words and phrases, I have never felt more at home than when I am dining in a French restaurant in France. (Lest you think me delusional, I can claim a fairly rigorous command of menu French — in comprehension if not conversation.)

“My Burgundy” puts me at ease even before we’re seated. The greeting may be in French (and they easily peg us as tourists), but they still ask (in jovial, broken English) if we prefer sitting outside (facing the gorgeous Place des Vosges), or inside, where the view may not be as spectacular, but neither do you have a highway of pedestrians jostling your table. We have the usual foggy-headedness from fourteen hours in an airplane, so it is comfort food we seek when ordering and we head straight for the classics.

The fresh-cut tartare and some gorgeous smoked salmon hits the table while I am bloviating on the virtues of the house wine (50 cl of dense, grapey St. Emilion for 24 euros), as the groggy Food Gal feigns interest through sleepy eyes and soaks up some wine, and the atmosphere.

She finds additional solace in a soothing oeufs en gelee (another impossible-to-find dish on this side of the pond), and even after we’re stuffed and sleepy, we can’t resist the gossamer charms of an île flottante:

Less than three hours after touchdown, we feel like we’re right where we’re supposed to be.

We then trek back to our digs at the Grand Hotel du Palais Royale — one of the best-situated hotels in all of Paris — before resting up and strapping up for, you guessed it, dinner.

Only a few blocks from our hotel is the candy store for cooks known as E. Dehillerin, which is a stone’s throw from Rue Montorgueil (below) — a pedestrian-friendly street where scores of cafes/bistros/restaurants beckon for a mile.

Stroll another ten minutes south and you find the cacophonous wonders of Les Halles and the Marais in one direction, or the beginning of the trés chere shopping district along the Rue Saint-Honoré, in the other.

Rue Montorgueil (pronounce Roo Montor-GOY-a) is filled with joints like this below, all of which tempt you to sit and watch the world go by, or plan your next three meals from a cozy table nursing a cappuccino:

We’ll get to dinner in a minute, but first some oyster discourse …another reason to hit Paris in April before the season ends.

OYSTER INTERLUDE…or PLEASE EXCUSE OUR SHELLFISHNESS

France is the oyster capital of the world, and 80% of all oysters raised in France are consumed within the country. People used to American oysters — even the good ones from Cape Cod and Washington State — are in for a saline surprise when they slurp their way through these tannic-vegetal-metallic wonders, best described as licking a penny under seawater. April is the last great month of the year to get your fill of these briny bivalves, so consume by bucket-load we do.

They are sized by number on menus in inverse relationship to their heft: No. 6 being smallest, while 000s (nicknamed pied de cheval – horse’s foot) are big boys for those who love swallowing their fleshy/slimy proteins in tennis ball portions. We look for fines (small-to-medium) Ostrea edulis (called plates, flats or Belons, even though they don’t always come from Belon, yes, it’s confusing) usually in the No. 3-4 range, and always from Brittany, as these are the most strongly flavored (and usually the most expensive). If you like your molluscs on the sweeter side, look to Utah Beach.

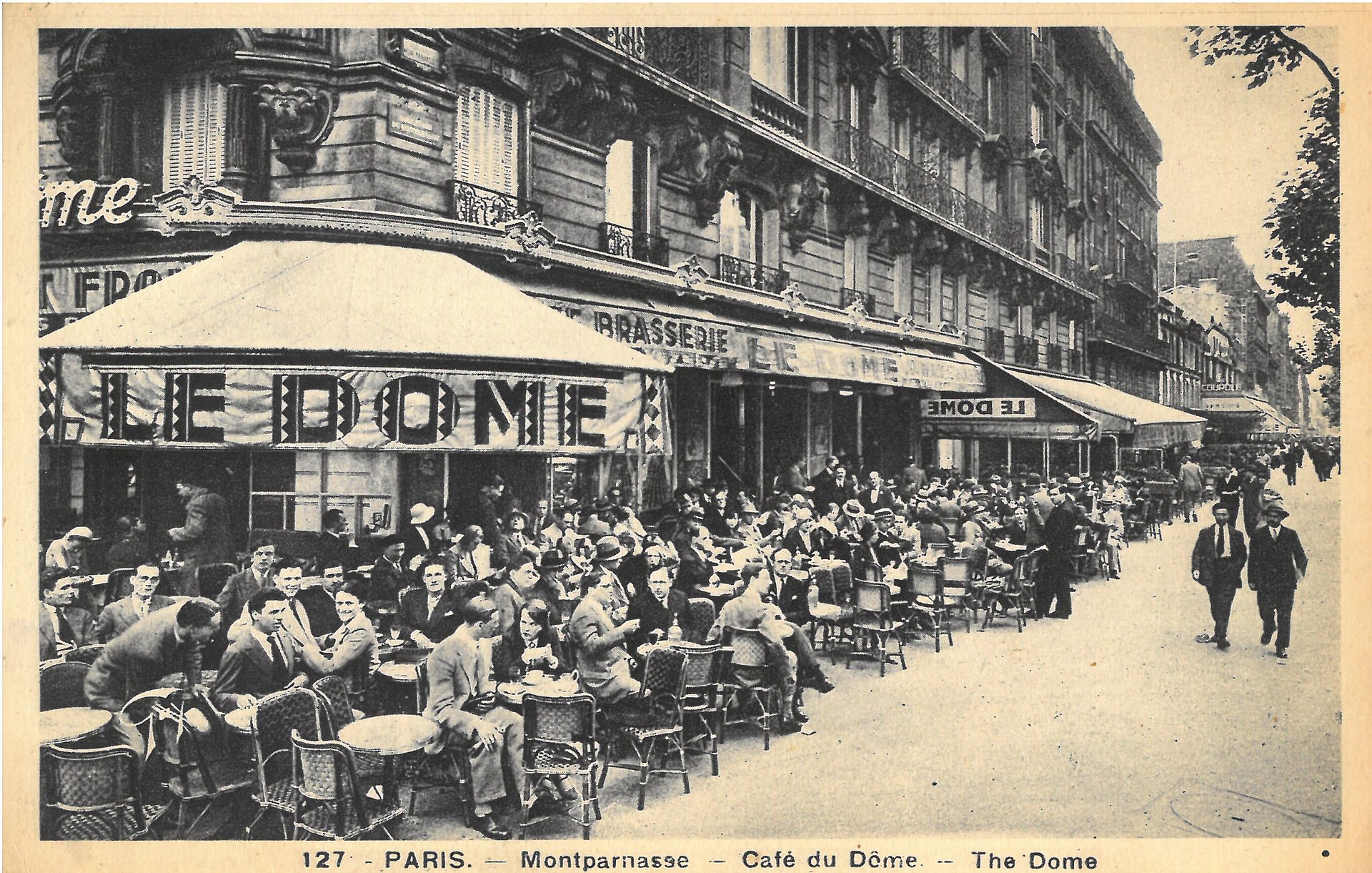

Unlike America, oysters in France don’t travel far from seabed to table, so when you polish off a douziane at Flottes or Le Dôme, you will be so taken by their intensity, you’ll forget about how silly you sounded trying to order them in French.

(JC’s Senior trip pic)

(JC’s Senior trip pic)

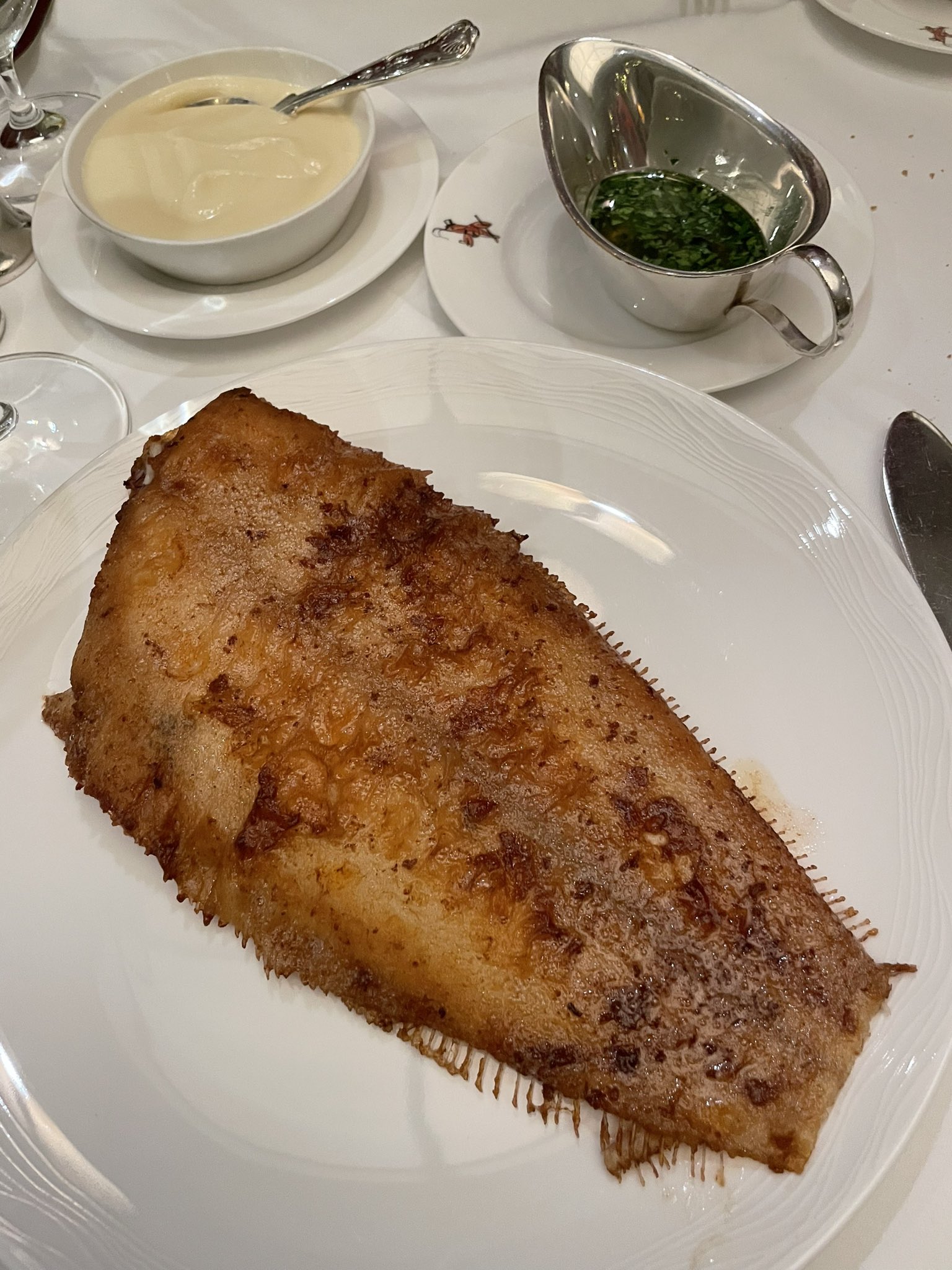

One does not live by oysters alone, so at Le Dôme Café one orders them solely as an entry point for a seafood feast amidst an old-school, brass and glass decor that would make Pablo Picasso feel right at home. The look may be classic, but it has aged like a soft-focus painting from the Belle Époque, and the service could not be better. The Dover sole is the standard by which all others are measured. Its firm, sweet, succulent nuttiness puts it on a level worth flying an ocean for:

TAKE A HIKE

The language of France may have defeated me, but the streets of Paris have not. Various map apps have turned the city from intimidating into a walkable wonderland.

In the past, we thought nothing of taking cabs or the Metro between sites and neighborhoods. Now we hoof it everywhere. Most of what a tourist wants to see (and eat) is within a three-mile radius of the First Arrondissement, and if you dress for urban hiking (thick, comfortable soles are a must), you will walk off those croissants in no time. And if you like to toggle between the Left and Right Bank (as we do), you’ll become as familiar with the Tuileries as your own back yard:

Exercise is but a side benefit of all the sightseeing done much better on foot. Cars move too fast, and the Metro shows you nothing but your fellow sardines. Walking is the best way, the only way, to properly absorb the mood of a city. Even the ugly walks can be worthwhile; schlepping from the Trocadero to Saint-Germain-des Prés (if you don’t walk along the Seine) is one stolid grey block after another, but you get a feel for everyday Parisian life that you will never see if you stick to the tourist/scenic routes.

Five-to-ten miles a day is a snap for us these days, and a necessity when calories entice at every corner. In my younger years (when ostensibly I was in better shape), I wouldn’t have considered walking from the Eiffel Tower to Les Halles. Now, as an aging boomer, I see that it is less than three miles (2.8 to be precise), and take off without a second thought.

The equation is simple: Urban hiking + bigger appetite – fear of gaining weight = more restaurants to explore.

SO MANY CROISSANTS

Our croissant quest began one morning at Stohrer — the oldest patisserie in Paris — and another at Ritz Le Comptoir: two ends of the pastry spectrum: one as traditional as they come; the other, a modern (perhaps too modern) take on puff pastry as you’ll see from the not-very-classic pain au chocolat below:

Neither of the above was the best croissant we had in our 17 days of patrolling the streets of Paree. We went high; we went low. We even went to a so-not-worth it 170 euro brunch at the Hotel Le Meurice which featured a tsunami of small plates aimed at the Emily Shows Off In Paris crowd.

The meal had more moving parts than a Super Bowl halftime show, and like whatever the f**k this is:…was more concerned with choreography than harmony.

To be fair, its croissants were mighty fine even if they were linebacker-sized. (Any mille-feuille aficionado will tell you what you gain in girth, you lose in finesse — sorta like football players):

Side note: the Meurice was one of the few places we encountered women as servers. Waiting tables in Paris (from the lowliest cafe to temples of haute cuisine) remains a valued profession very much dominated by men. Which is one of the reasons service is so good.

I kid. I kid…

As for our best crescent roll we tried, that honor goes to an award-winner from La Maison d’Isabelle — which won best in show at some hi-falutin’ bake-off a few years back. In our contest, it was the compact, pillow-soft butteriness (encased in a delicate, easily shattered shell) that separated this laminated beauty from the also-rans.

People were lined up every morning for them, as they were taken directly from the baking sheet to the oven to your hand: the kind of only-in-Paris experience that spoils you for French pastries anywhere but here.

THE OFFAL TRUTH

The offal truth is you can’t find “variety meats” hardly anywhere in America. Americans have no compunctions about inhaling hamburgers by the billions, or polishing off chicken breasts and filet mignons by the metric ton, but put kidneys, sweetbreads, or brains in front of them and they recoil faster than a vegan at a hot dog stand.

This is where the classic restaurants of Paris come in to sate you with pleasures of holistic animal eating. As in: if you’re going to slaughter another living thing to keep yourself alive, you should respect the animal’s sacrifice and make the most of it.

Europeans are much closer to their food, both geographically and intellectually, and that relationship broadcasts itself on the menus of Parisian restaurants older than the United States.

To give you an idea how old Le Procope is, they have a plaque out front (just above The Food Gal®’s noggin in the above pic) celebrating customers going all the way back to Voltaire, who, as you recall, died in 1778.

Whatever fat he and Jean-Jacques Rousseau chewed here is lost to history, but no doubt one of them was rhapsodizing over Procope’s blanquette or tête de veau when they did so. Three hundred and fifty years later, this 18th Century artifact (the oldest café in Paris) still delivers the goods, with cheery, old world panache, to regulars and tourists alike, at remarkably gentle prices.

Our “calves head casserole, in 1686 style” was about as hip as a whalebone corset, and all the more delicious for it. Besides being the most wine-friendly food on earth, it is also the most elementally satisfying. No tricks, no pyrotechnics, just foods to soothe the savage breast.

Having successfully tackled a veal head, it was time to go scouting for lamb– at a cheese shop/restaurant perched atop the tony Printemps store near the Palais Garnier, of all places.

Laurent Dubois is reputed to have the best croque monsieur in all of Paris, so we escalated to his cheese-centric spot for a jambon et fromage, but ended up swooning over the navarin (stew) loaded with tender morsels of lamb napped with electric green baby peas in a mint-lamb jus sharpened by jalapenos:

On the cuisine bourgeoise level, this was the dish of the trip.

As good as the stew was, we were hunting bigger game. So we strolled through a spring drizzle to Le Bon Georges, a temple of bistronomy which combines classic technique with terroir-focused creativity, hyper-seasonal ingredients, a killer wine list, and very informal but informed service — all squeezed into a cramped, casual space. Like all in the bistronomy movement — the food was simple but surprisingly intense.

Service is by kids who may look like teenagers (with big, patient smiles), but you can tell they are no strangers to dealing with out-of-town gastronauts with all kinds of accents. The chalkboard menu tells you all you need to know (they will happily explain a poussin (baby chicken) from a poisson (fish) to the clueless), and the wine list is Michelin-star worthy in its own right, at prices far gentler than what you’ll find at tonier addresses.

The noise level is tolerable (we were in a back room closer to the kitchen) and the chairs were actually comfortable (not always a given). Describing the food as gutsy doesn’t tell half the story.

Clockwise from above left: duck paté en croûte with foie gras and prunes; smoked trout with orange sauce; morels with grilled onions, napped with Comté cheese/vin jaune sauce; and white asparagus smothered in vinaigrette, just the way we like them. And these were just the starters.

From there we proceeded to roast duck with carrot puree, sweetbreads over potatoes, and daurade royale (sea bream) with a citron/saffron sauce. We finished the meal with baba au rhum, soaked with booze drawn with a pipette the length of your arm from which you suck just enough libation from a humongous bottle (containing your spirit of choice) to bring it to your glass. Over the top? Of course, but also effective in sending everyone home with a happy glow.

We also got quite the show from chef Lobet Loic as he broke down a cow udder to include in a vol-au-vent concoction he was working on for the next night’s dinner.

https://twitter.com/i/status/1646381805308657665

“Just when I thought I’ve tried every part of the cow,” one of our social media followers observed. Us too. This was a new one for even an all-animal appreciator like yours truly.

Even our very French waiters told us it was a part of the animal they had never seen broken down for consumption. They were just as amazed as we were.

LISTING DU PORC

Our hunt for oddball animal parts was hardly over after Le Bon Georges and Procope, so to Le Comptoir du Relais Saint Germain we trotted the next day to make a swine of ourselves over Yves Camdeborde’s crispy, rib-sticking pied de cochon:

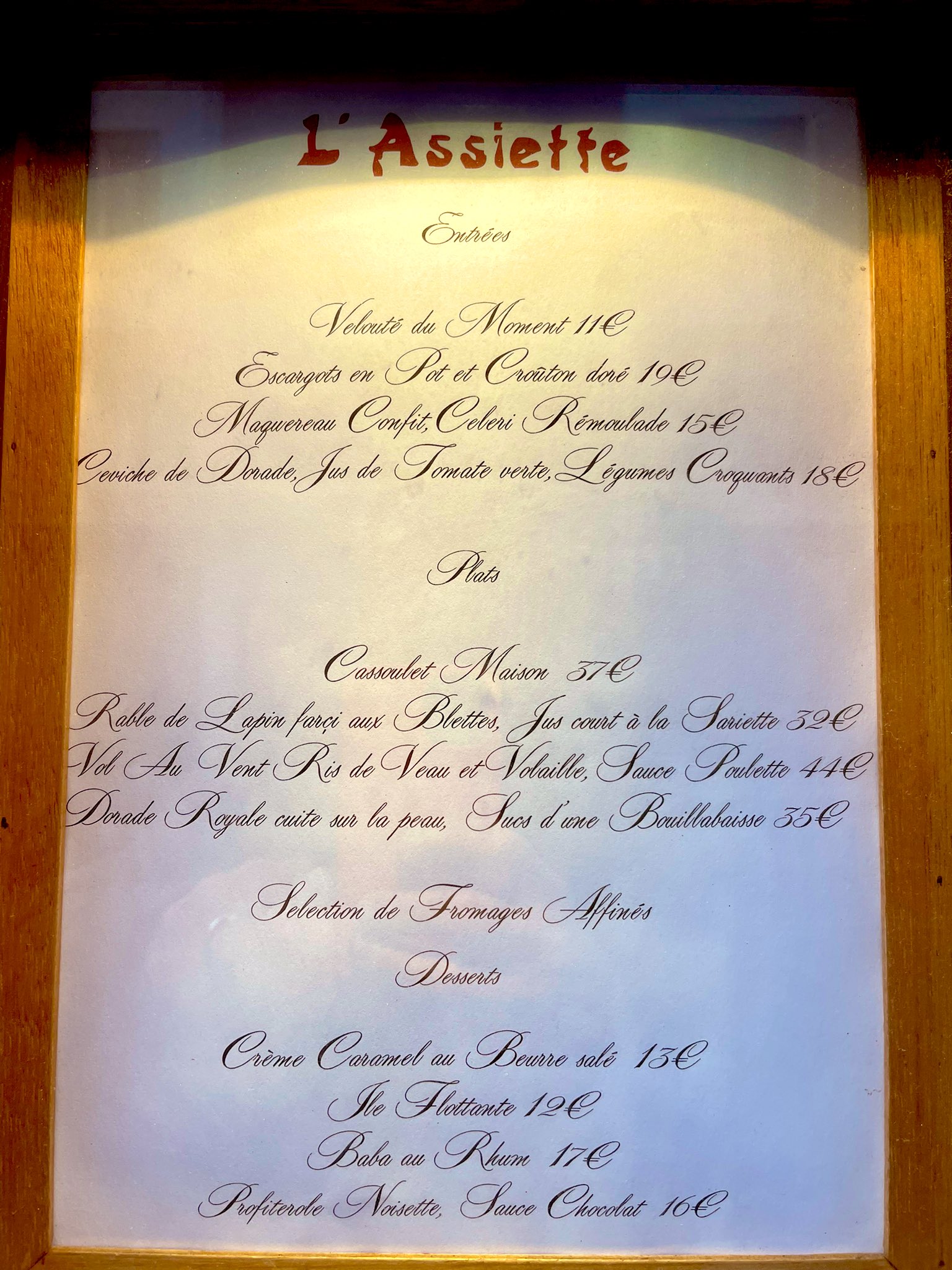

Then there was a trek to the far reaches of Montparnasse to try what many call the best cassoulet in all of Paris. (An honest cassoulet being harder to find in America than an authentic choucroute…or a toothsome lamb stew on top of a department store for that matter.)

L’Assiette (“plate”) has received this accolade from Paris by Mouth, who knows her way around a Tarbais, and the version we had in this non-descript spot was so dense with meaty/beany flavor all we could do is quietly thank her in between mouthfuls.

L’Assiette is the ultimate neighborhood gastro-bistro, so small (we counted 24 seats) and so far off the beaten path that nudging your way past Instagrammers will not be a problem. Even as strangers, our welcome was as warm as those bubbling beans, and as soothing as the Languedoc-Roussillon red wine (Domaine Les Mille Vignes Fitou Cadette) that hit the spot on a chilly night.

Choucroute can go stuck rib to stuck rib with cassoulet, which is why this apotheosis of pork beckons us like a holy grail, and why we usually make a beeline to old reliable Brasserie Lipp to demolish a platter at least once every trip.

We’ve always been in Lipp’s thrall — from its 19th Century vibe to the burnished wood and ever-present cacophony — it is a restaurant where time seems to stand still.

We even enjoy the narrow, elbow-rubbing two-top tables that are so cramped, they make flying coach on Spirit Airlines feel like a private jet.

And we’ve always found the service to be the opposite of the bordering-on-rudeness reputation of the place. Even now, they gave our brood of six the best table in the house for a late lunch without reservations, and our aging waiter couldn’t have been nicer. (At Lipp, “aging waiter” is a redundancy, since some of them look like veterans of the Franco-Prussian War.)

This time, we loved everything about it…except the food.

Lipp’s jarret du porc (above) used to be de rigueur on every trip. This time, like most of our meal, it was disappointing, The portent came from a too-cold house pâté, then succeeded by a slapdash Dover sole and then the chewy pork knuckle, Everything felt perfunctory. Even worse, this “Alsatian” restaurant had but four wines from Alsace on its list. Wassup with that?

Perhaps it was an off day, but the food looked and tasted like no one in the kitchen cares anymore….which is what happens when social media ruins your restaurant.

Luckily, good ole Flo restored our faith in the flavors of Alsace.

If Lipp is getting worn around the edges from over-popularity, Brasserie Floderer is holding its own in the sketchy 10eme Arrondissement. — perhaps for the opposite reason. To get there on foot, however, you’ll have to pass some pretty dodgy blocks and trip over lots of kebabs. You know things have taken a turn for the worse, we thought to ourselves as we surveyed the chickpea-strewn streets, when the falafel stands start popping up.

Against this backdrop of littered streets and skewered food, Flo shines like a beacon from days gone by:

The interior feels like a movie set (above) and the menu is as no-nonsense as the 1909 vintage decor.

As the most stubbornly Alsatian of the remaining brasseries, the Franco-German classics check all the boxes: celery root salad (here cubed not shredded), textbook onion soup, and a “Choucroute Strasbourgeoise” of tender pork belly (poitrine fumée), spicy kraut, smoky sauccisse cumin, a second sausage (Francfort) – because a single sausage choucroute is akin to sin when “garnishing” this cabbage.

In case you haven’t had enough pork, there’s also a big hunk of shoulder (échine) to finish you off. How something so fundamental can feel so fresh for so long is a secret known only to Alsatian cooks. They also do a seafood choucroute here, named after Maison Kammerzell — the venerable brasserie in Strasbourg — but we were too busy pigging out to try it.

Brasserie Flo wasn’t the best meal of the trip. It wasn’t even in the top five. But there was something deeply satisfying about returning to a restaurant, far from the madding crowd, where locals still value out-of-fashion recipes for their pure deliciousness.

Which is why we never tire of Parisian bistros, brasseries and cafés — places with deep roots in country cooking, which have withstood the test of time, and stand in proud opposition to the cartwheels-in-the-kitchen gymnastics of fusion food…and so much falafel.

This is the first part of a two-part (perhaps a three-part) article.

(Ramsgate at night)

(Ramsgate at night) (Chippee kay yay)

(Chippee kay yay) (How do you say ‘Hell ya!’ in British?)

(How do you say ‘Hell ya!’ in British?) (Luxuriating in Langoustines at Wilton’s)

(Luxuriating in Langoustines at Wilton’s)

(BiBi = Indian nana)

(BiBi = Indian nana)

(Banger? I don’t even know her!)

(Banger? I don’t even know her!) (Duck! And order another manzanilla!)

(Duck! And order another manzanilla!)

(Tiny tables, quality cooking)

(Tiny tables, quality cooking) (Small table, big flavors)

(Small table, big flavors) (British beef)

(British beef) (British spuds, French technique)

(British spuds, French technique) (Tastes like hazelnuts, not salty, stale fish)

(Tastes like hazelnuts, not salty, stale fish)

(Quite the pisser, these bad boys were)

(Quite the pisser, these bad boys were) (No humbuggery here)

(No humbuggery here)