Before we leave 2021 in the rear view mirror for good, a few words on what will be our last year of eating hugely.

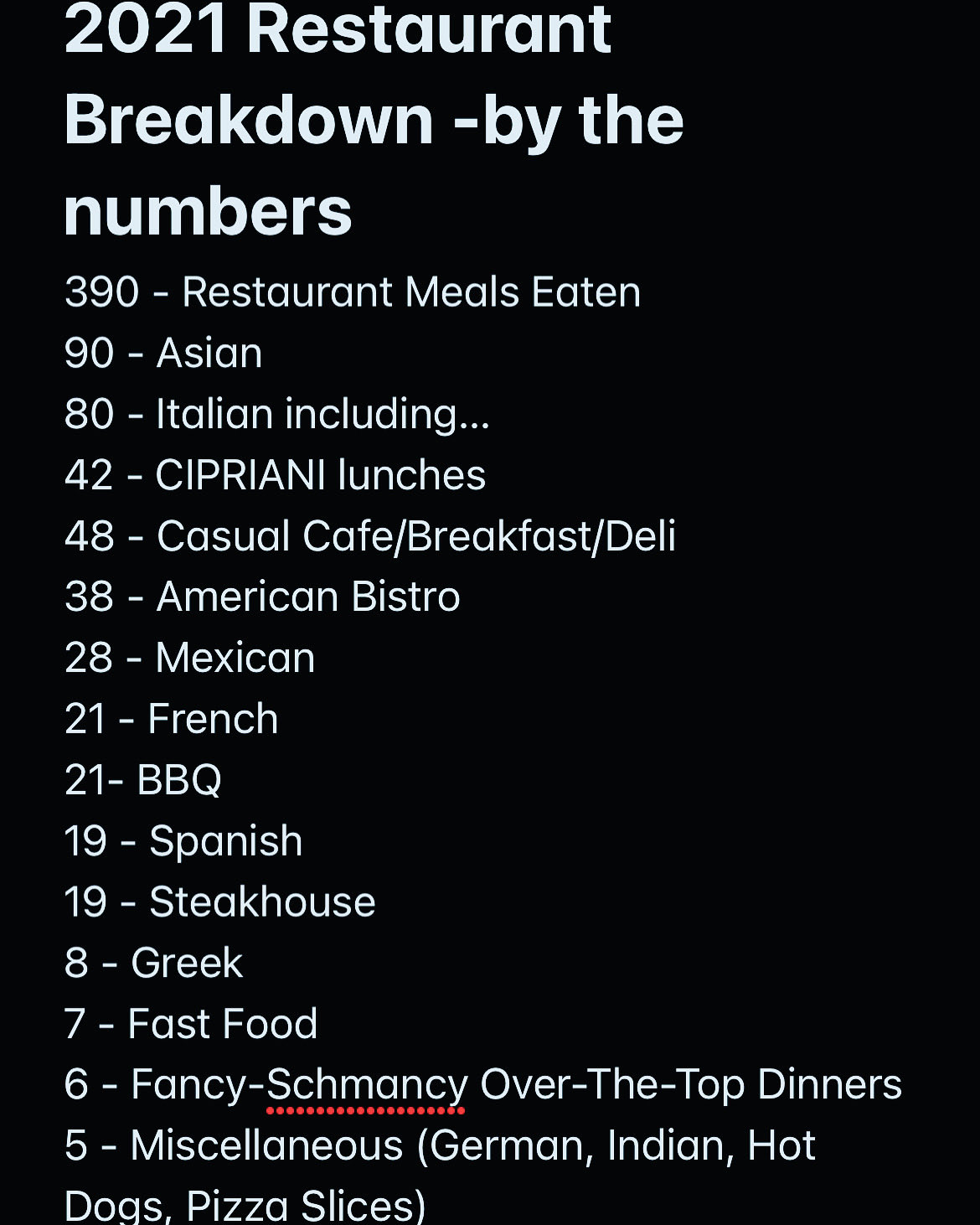

As you can see above, we hit 390 restaurants last year — by our standards a light one, even though we were far busier than in 2020, when the world conspired to put food service permanently out of business and almost succeeded.

During our salad days of 1995-2015, 390 restaurant meals wouldn’t have broken a sweat. Back then, 500/year was the norm, as we hunted high and low for the best grub in Vegas. From 2010-2020, EATING LAS VEGAS – The 52 Essential Restaurants kept us in the game until everything ground to a halt.

Now, we write for ourselves and for fun and for the hundreds and hundreds of you who actually still care about such things as finding the best restaurants (high and low) in which to spend your hard-earned dollars. Our staff told us last week we now average about 1,000 unique views a month. Quite a drop from the “good internet” days of 2008-2014, when 100,000 folks would tune in. No matter, at this point we’ve downsized (voluntarily or not), and starting this year, that’s the way we’ll be eating.

With that said, here are some final thoughts on our weirdest restaurant year ever:

90 Asian meals! This should be no surprise to anyone who follows me on social media. Spring Mountain Road, along the new mini-Chinatown springing up on South Rainbow, is our default setting for eating out. When the question is, “Where should we go tonight?” and the The Food Gal sighs “I dunno,” we head to Chinatown without hesitation and dive in to whatever suits our fancy…BECAUSE its eazy-peazy, inexpensive, healthy, honest food, usually served by family-owned establishments who spend more time in the kitchen than on social media.

Of those 90, almost half were Japanese, with Chinese in second place, and Korean in third. Bringing up the rear were Thailand, Vietnam and (shudders) Malaysian — the charms of which continue to rank somewhere between canned chow mein and Panda Express.

How much Asian do I eat? I eat so much Asian my nickname is Woo-Is-He-Fat. I eat so much Asian my wife calls me a hopeless ramen-tic. I tell her she means so matcha to me, and I can’t stop thinking bao her, and she tells me I’m tofu-rific and she’s crazy pho me. (This causes things to get steamier than a Mongolian hot pot.) Our Chinese friends ask us, “Har Gows it?” while our Korean buddies always want to know, “Sochu wanna hang out?” We eat so much Asian The Food Gal’s favorite sex toy is a Japanese rice cooker. (Wait. What?) Yeah…we eat a lot o’ Asian. ;-)

80 Italians? Are you friggin’ kidding me? We knew it was a lot but had no idea until the totals were run. Of course our regular Friday Cipriani lunch was almost half the total, but even if you back those out, that’s a helluva lot of pasta, pizza, antipasti, primi, secondi and contorni. 80 Italian meals is too much….unless you live in Italy. So you’ll pardon us if we say we’re pretty much over Italian for the time being. The next time we eat this food….I hope to be in Italy, not suffering through another local, oversized/underseasoned version of cacio e pepe.

48 “Casual” meals — included everything from a bagel sandwich to coffee and croissants. Deli comprised almost half of that as we hit everything from PublicUs to Bagelmania to Saginaw’s to Life’s A Bagel with the enthusiasm only a non-Jew-wannabe-Jew like yours truly can have for this food. Our deli choices improved in 2021, consigning Bagel Cafe to an even lower-level of Jewish food suckitude than it already holds .

38 American Bistro — includes everyplace from Main Street Provisions to burger joints to the execrable Taverna Costera — the latter of which was so terrible it coulda/shoulda gotten our “Worst Meal of the Year” major award…but was so pathetic we didn’t deem it worthy of further insult. You could also call these places gastropubs: cozy, food-forward joints like 7th & Carson, Carson Kitchen, Ada’s Wine Bar, and Sparrow & Wolf. All have thrived despite the challenges of the past two years. Sometimes I wish some would dial things back a little more — adding to their menus by subtraction — but if you’re looking for good cooking in the ‘burbs, our home-grown bistros are where to start.

28 Mexicans means mas mucho macho grande burritos and tacos, muchacho. (We probably ate more tacos this year, here and in Los Angeles, than in the previous five journeys around the sun. 2021 also saw our last meal ever at the sad, straight-from-a-can Casa Don Juan. “Never again,” we muttered as we paid a $40 check for a lunch that wasn’t worth half that. Used to be charming service pulled this place through. That’s gone too. Walk down to Letty’s and get yourself a taco. You can muchas gracias me later.

Kinda funny we only hit 21 French meals, considering that it’s our favorite food in the world. Limited hours at many of our famous frog ponds are to blame (Robuchon, Guy Savoy, Le Cirque..), and the merry-go-round of chefs at Marche Bacchus put us off as well. (Side note: We’ve also lost several players — Gagnaire, Boulud, Hubert Keller — who brought Vegas some very serious French cache back in the early aughts.)

For the survivors, things are still not back to pre-pandemic normalcy, but are improving. MB has enlisted that old Gallic warhorse Andre Rochat to revamp its menu and turn it into what it should be: a serious French bistro. A bold move, long overdue, which we applaud, even if my relationship with Andre has sometimes resembled the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.

The home stretch…

We traveled back to the southeast four times in 2021, which explains our 21 BBQ meals.

The armada of Spanish (19) in town (EDO, Pamplona, Jamon Jamon, Jaleo, Bazaar Meat), accounts for our Iberian intake, and visiting a Steakhouse (19) about twice a month also feels about right…although we’ll readily admit that, as with Italian, we’re getting bored with all the by-the-numbers menus of wedge salads salmon, and identical steak cuts. CUT and Bazaar Meat are the only joints that break this mold. Long may their cholesterol flag fly.

Bringing up the rear we have Greek (8), almost entirely at either Milos or Elias Authentic Greek Taverna, and Fast Food (7) which generally consists of Shake Shack, In-N-Out or the (seriously underrated) Double-Del Burger from Del Taco.

Finally, there are Fancy-Schmancy Meals (6). What stuck out for us when we were making our final tally was not only how few there were, but that every one of the year’s most impressive meals was out of state. FWIW: nothing we ate in Vegas, in 2021, held a candle to to our dinner at Providence (L.A.), the precise cuisine of Gavin Kaysen at Spoon & Stable in Minneapolis, and the steaks and sides we had at Totoraku (L.A.) and Manny’s in Minneapolis.

True confession time. What the above meals drove home to me was something I’ve been holding back from saying for years: much of what Vegas’s top restaurants do may be good, but it still isn’t as good as the similar work being done in other cities, and you’re fooling yourself if you think otherwise. There are many reasons for this — from more demanding diners to access to agriculture — but the well-traveled palate can tell the difference. Our Mexicans aren’t in the same league as Southern California’s, our gastropubs aren’t as finely tuned as Washington D.C.’s, and our barbecue and pizza scenes (as improved as they are) still lag far behind those in bigger cities.

And our steakhouses, for all the money poured into them, still feel like food factories compared to America’s classic beef emporiums.

Have I been guilty (for years) of overpraising places in the name of provincial boosterism? Absolutely. But as I get older, and my time and calories become more precious, I want to spend my appetite in places where the cooking is more connected to something other than an Instagram page. It’s one of the reasons you find me in Chinatown so often, enjoying simple Asian fare over the more convoluted cooking being done by the cool kids.

Vegas has always been the sort of place where people stay just long enough to make enough money to leave, and too many of our local restaurateurs seem to be in it for the cash, not the passion. Quite frankly, I’m surprised so many young chefs have stuck around once they leave the Strip. But the play-it-safe-and-cash-in mentality remains strong (e.g. Harlo, Carversteak), and there’s not enough demand here for simple, sophisticated food. The Japanese and Spaniards get it right….but few others do.

So, that’s the final chapter on 2021. The direction this website takes in 2022 is anyone’s guess. When the muse hits me, I’ll write…because I love to write when she visits. In the meantime, we’re off to France for a couple of weeks to re-calibrate the palate, refresh the mind, and forget about America for awhile. Bon appetit to all and Happy New Year.

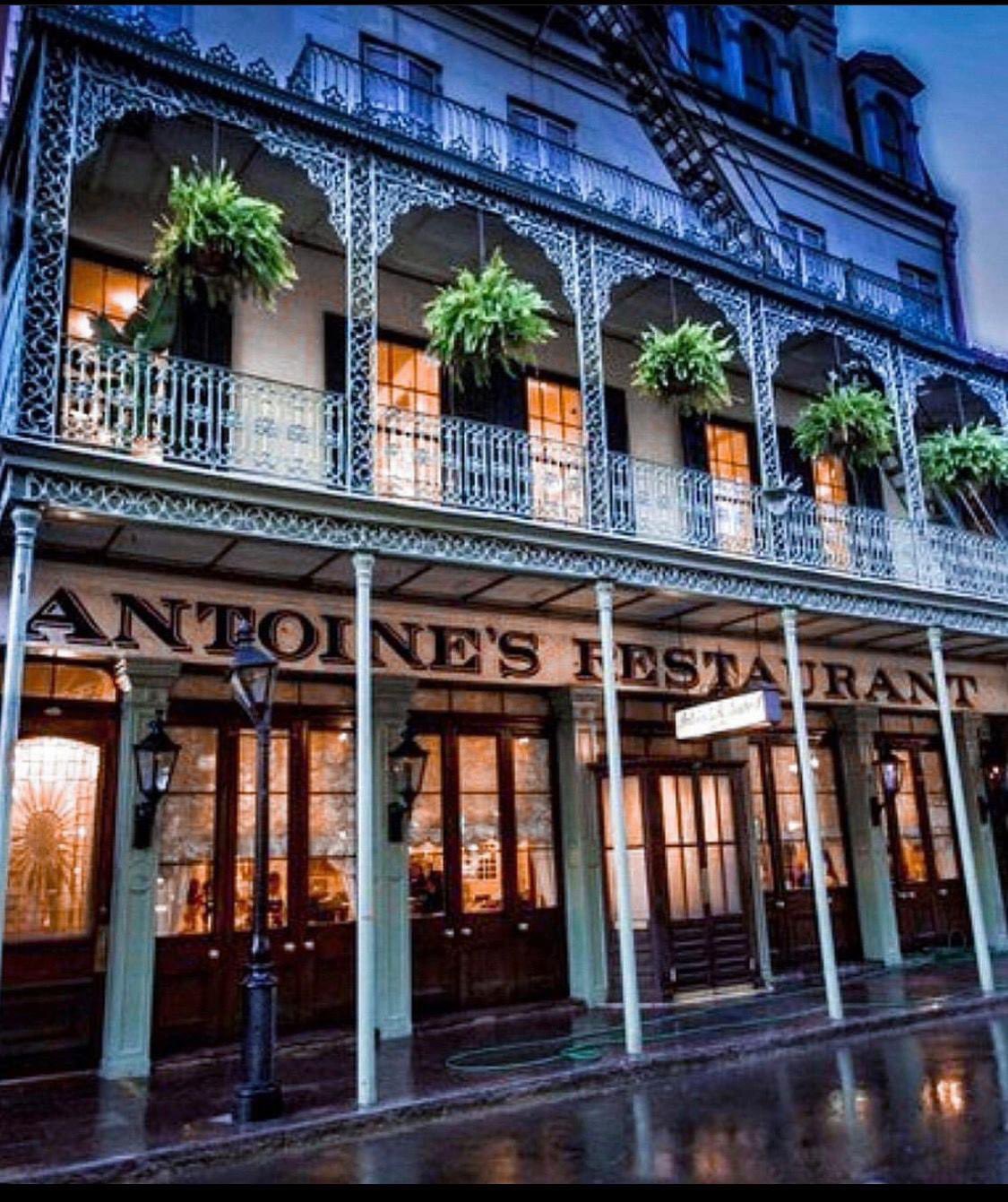

(Where we ate in 1958)

(Where we ate in 1958)

(With LT in Gay Paree)

(With LT in Gay Paree)

(Canocce – Mantis shrimp)

(Canocce – Mantis shrimp)

(Keep drinking and carry on)

(Keep drinking and carry on) (Duck confit with summer vegetables)

(Duck confit with summer vegetables)

(Pan-fried Dorade with mussel tortellini and artichoke purée)

(Pan-fried Dorade with mussel tortellini and artichoke purée) (

( (aka grapes in vanilla cream sorbet in meringue crust)

(aka grapes in vanilla cream sorbet in meringue crust) (Crab “Napoleon” with lobster sauce)

(Crab “Napoleon” with lobster sauce) (Tomate stracciatella, crémeaux basilic poundré à l’olive noire – but you knew that)

(Tomate stracciatella, crémeaux basilic poundré à l’olive noire – but you knew that)