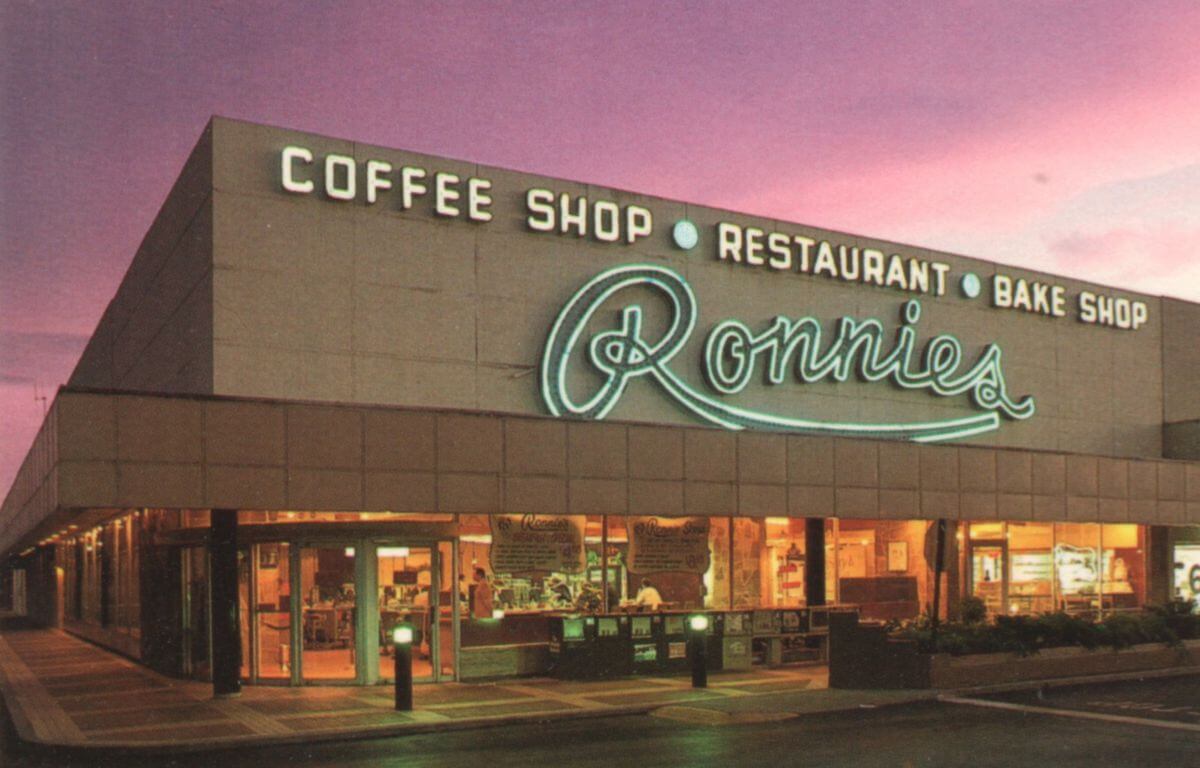

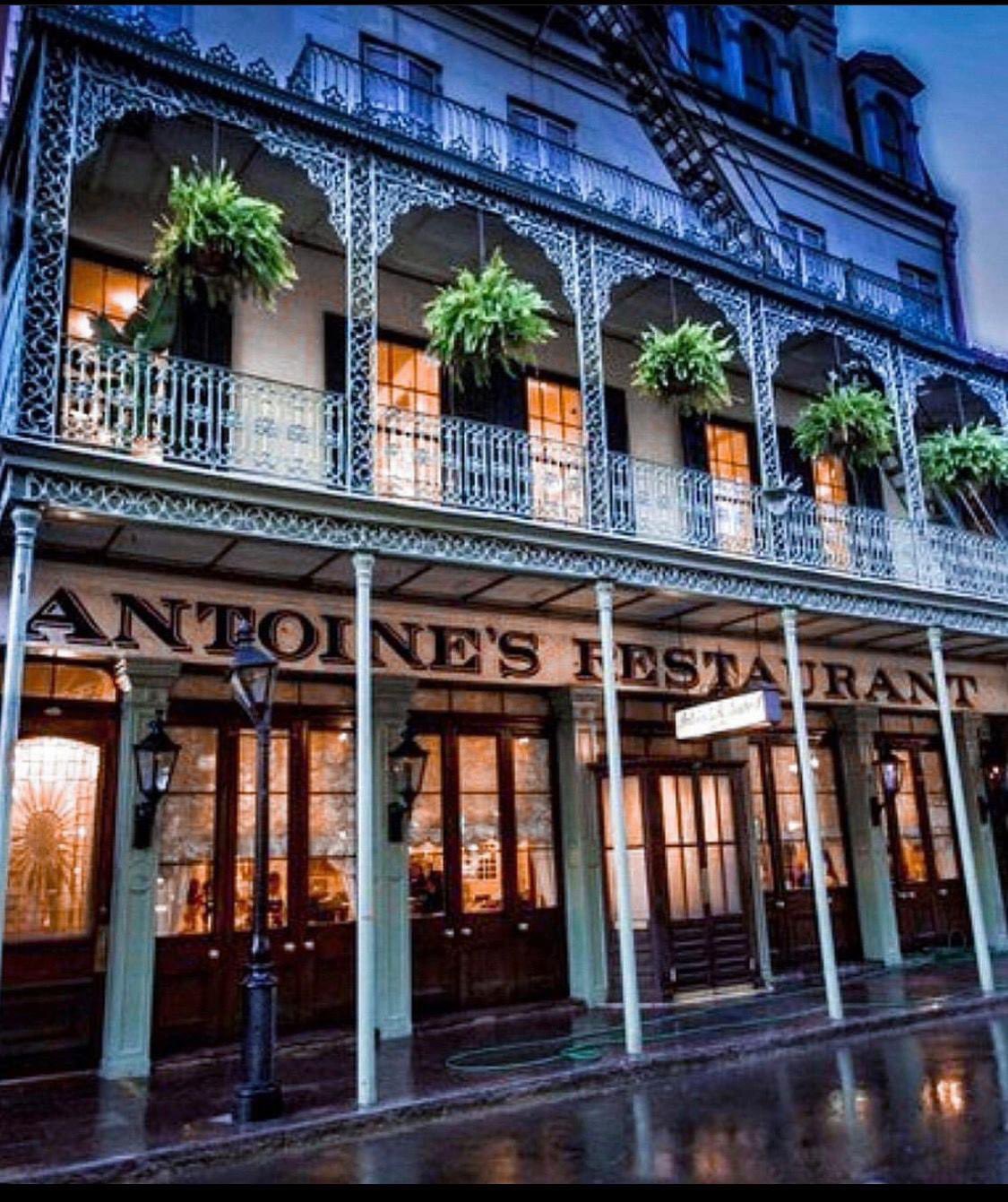

Epiphany (noun): an illuminating discovery, realization, or disclosure Ask any food writer how they became interested in food and they will point to an epiphany, or perhaps several, that spurred them into a life of obsessions. Here are a few of mine: People are always saying Antoine’s (est. 1840) isn’t as good as it used to be…which is something people have been saying since the Civil War. Be that as it may, this New Orleans institution gave a 12-year old his first taste of extraordinary cooking when it placed a bubbling, sterling silver oval, about the size of a large candy dish, in front of him in the mid-60’s. Filled with lump crab meat it was, spitting and gurgling sherry-tinged butter from its elegant confines. “Why don’t you cook like this?” the 12-year old asked his mother. They all had a giggle, the butter gurgled, and the boy gulped it all down. You never forget your first time, he has often thought to himself in the ensuing half-century — with booze, drugs, sex, or crab meat bubbling in sherry butter. Before there was Antoine’s, though, there was fresh-baked bread and apple butter at Grandma’s knee. In Wexford, Pennsylvania, just north of Pittsburgh, where yours truly first entered this mortal coil, he often visited his grandparents as a mere tyke. Sometime, as a little shaver (probably not more than 6), he recalls standing beside a huge white stove, his grandma (a big woman) standing there with her giant arms, slicing him a piece of bread right out of the oven, and slathering it with her homemade apple butter. Growing up in the 50s and 60s, bread was something with the texture of cotton balls you got out of a plastic bag. My grandma (Hazel Brennan Schroader) taught me that it wasn’t, but it would be another 20 years before I would taste bread as fresh or as good, and back then (the 70s) I had to make it myself. “This is the best tasting thing I’ve ever put in my mouth,” is what the young pre-teen thought when he first encountered barbecuesauce — that heady mix of ketchup, brown sugar and assorted spices which is as common as ketchup now, but was a rare and exotic thing back in the day, outside of the barbecue belt. To this day, after eating ‘cue across the country, and making everything from brisket to hot vinegar sauce from scratch, we still hold a special place in our heart for the standard, Kraft-level, sugary stuff. P.S. Stubb’s make a fine one.  One wouldn’t think a pumpernickel rollcould make such an impression, but the one’s at Ronnie’s in Orlando, Florida set a standard that is yet to be equaled. About the size of a small woman’s fist, these dark-brown, double-folded beauties were filled with finely-chopped, melted onions, and possessed that malty, dark-roasted tang most brown breads can only dream about. And dream about it to this day I do– with smiling thoughts of eating them at home or in this booth (below), which my dad commandeered for our family of six almost every Sunday.

Her name was Syndie and she was small, cute, fair-skinned and raven-haired and I was totally in love with her for about twelve minutes in 1968. On one of our first dates we went to Arby’s. Yeah, that Arby’s — the one with sandwiches made with a compacted brown substance having more in common with cardboard than actual meat. But this wasn’t always the case. In fact, the case at the early Arby’s were filled with actual roast beef, from which they would finely slice and pile high the ribbons of rib eye that would make this place a success. Like the original McDonald’s, or the smashed, caramelized steakburger of Steak n’ Shake fame (two other epiphanies), the original Arby’s sandwich was a revelation in tasty fast food. Alas, they all have as much in common with the edibles that put them on the map as a cafeteria has with haute cuisine. My first experience with oysters was with a college buddy named Bill Bardoe at a place called Lee ‘n Rick’s Oyster Bar in Florida, if memory serves. Don’t know what happened to ole Bill, but still thank him for turning me on to these beauteous briny bivalves back in my college days. Try them steamed, Bill advised, and he had a point. To this day, it is how we prefer oversized Gulf oysters. Oyster epiphany #2 happened in Brussels two decades later — where the small, flat, coppery Belons (above) were so fresh they contracted when hit with a drop of lemon juice. These have been my holy grail of ‘ersters ever since. Only in Paris have I come close to re-creating such perfection.  Nantucket seafood is its own thing: straight from the boats onto your plate, at a phalanx of restaurants with the coin and clientele to treat it right. Nowhere in the United States have I found the bounty of the sea as succulent…although on a good day the Pacific Northwest comes close. Carnegie Deli corned beef — piled higher than a B-52, served by mock surly waiters — taught me more about New York eating than the Union Square Cafe and Lutèce ever did. Unlike most oenophiles, I don’t consider great wine with the reverence usually afforded it. Having had them all — from the classified growths to the Grand Crus to vintage champagne to the rarest of Rieslings — I have always kept it in perspective. Wine is a fermented grape beverage designed to be enjoyed with food, not fetishized like fine art. Screaming Eagle and DRC don’t taste that much different from bottles costing hundreds (thousands?) less. That said, a private Grand Cru tasting of Chablis in NYC, back in 1988 with winemakers named Dauvissat, Raveneau and the like was quite the palate opener, spoiling me for mediocre chardonnay forever.

For the epiphany of all French epiphanies, I heartily recommend spending two weeks in France with Laurent Tourondelsometime…eating in nothing but Michelin 2 and 3-star restaurants (see above). Gained 11 pounds. Was totally worth it. Christmas at Duran’s Pharmacy has nothing to do with the holiday season, and everything to do with red and green New Mexican chile (above). New Mexican food is its own thing: an amalgam of Native American, Mexican, and Southwestern cooking, and the lady Latino cooks at Duran’s do it as well as anyone. Sitting at the counter, and watching them work, is almost as lip-smacking as polishing off their definitive carne adovada. Our days of enduring marathon tasting menus are deader than Craig Claiborne. The spirit is willing but the flesh is weak for things like a four hour dinner at Le Grand Vefour. When we go haute cuisine hunting in France nowadays, it’s more likely to be at lunch than dinner. But way back when we were up for it all…including three-hour lunches followed by feasts that would make Lucullus blush. I’ve been back to LGV several times since that first meal in the early 90s, but it has stayed with me, right down to the perfume of truffles wafting from within a Bresse chicken, and slab of goose foie gras so silky it was like an Hermés scarf for your tongue.

Our first sojourn to the original Harry’s Bar in Venice was love at first taste — that taste being of Venetian seafood that seems to attain an unworldly sparkle from the Venetian Lagoon and surrounding waters. Croatians may carp, Norwegians say nay, and the Japanese take umbrage, but the simple creatures of Venice are, to my mind, the greatest seafood on earth, perhaps because of the elegant, elemental way they are prepared. Maison Troisgros is the finest French restaurant I’ve been to outside of Paris. So good I once accomplished a lunch-dinner-lunch hat trick there in a single 24 hours. Haven’t been back since, to my everlasting regret. That croissant outside of the Gare du Nord train station in Paris — 7:00 am on a freezing day and starving (after a night of carousing at Brasserie Flo), waiting for an early train back to Germany, I spied a lightedboulangerie a block from the station, just opened it seemed, with a few folks lingering outside in the morning chill. With time to kill I wandered over, drawn by the smell of fresh baked goods and patrons jockeying inside to get pastries directly from the oven. When it came my turn it was an easy order: “Un croissant et un pan au chocolat, s’il vous plait.” (Pretty much the limits of my French at the time; pretty much the limits of my French to this day.) The pastries were still warm when I took them out of the bag on the sidewalk. Their crusts were as thin as tissue paper, as brittle as spun sugar, with a bronzed sheen of uniform perfection. They shattered with the lightest of bites, scattering shards of butter-soaked mille-feuille all over my jacket and pants. I can still see the little spots of butter soaking into my clothes. Never had a croissant since that was as satisfying. The French practically invented the word epiphany (actually, the Greeks did), so it’s no surprise many of mine have come at their hands, including: L’Auberge de L’Ill’s carte des fromages. Getting engaged to The Food Gal at this venerable Alsatian 3-star was nothing compared to jaw-dropping, heart-fluttering effect of first seeing this multi-level cheese cart in 2005. Did I try one of everything? You know I did. Guy Savoy’s wild turbot, Lièvre à La Royale, and buckshot in the grouse. “I told you eet was freshly keeled thees morning, ” he beamed as we showed him the BB. Daniel Boulud’s masculine/feminine tasting menus, along with roasting a woodcock’s brain over a candle at Daniel. Yes, you hold it by the beak until the thimble-sized cerebrum starts bubbling. (Sorry, no pics, this happened during the Stone Ages – 2002.) Lexington, Texas has one of the best briskets in Texas at Louie Mueller’s; Lexington, North Carolina is chopped pork heaven with a host of local joints specializing in a simple sandwich. The whole hog rules in Ayden, N.C.. Until you make a pilgrimage to all of them (or at least one of them), don’t talk to me about your weak-ass, set it-and-forget it ‘cue. And then there were the Alpine cheeses of the Savoie at La Bouitte — Comte, Gruyère, Beaufort — whose nutty, creamy, concentrated fruitiness can only be fully appreciated when you’re gazing upon the pastures where the cows once grazed while you’re eating them with a glass of vin jaune. Prosciutto slices at Sabatini in Rome, where the slicing of each piece is treated with the delicacy of a straight-razor shave. Tortellini en brodo in Bologna, a dish so deceptively basic it almost comes as a shock when its soul-satisfying qualities threaten to overwhelm your senses. And finally, Cecilia Chiang’s minced squab lettuce cups, at the Mandarin in San Francisco, when you were but a neophyte feinschmecker, but one smart enough to know you were at the epicenter of a sea change in thinking about Chinese food. A lunch with John Mariani at the Ritz in Paris — the ideal gastronomic experience, where it was all about the conversation, the company, and the cuisine, with nary a false note on any front. Epiphanies come fewer and farther between as you age. As with sex, the ground doesn’t shake so often. But as with all life-affirming events, they stay with you. I suppose, that’s what these are all about: events seared in your memory as something so ethereal you can never forget them. An epiphany is always there, pulling, nagging, worming, tickling our thoughts with the sublime as we struggle with the corporeal and prosaic in our daily lives. Epiphanies give comfort that way — comfort and private little joys — soothing our souls while giving us the inspiration to carry on.

|

Author: John Curtas

Seymour Britchky

Except for a brief interlude in the 1940s, the Japanese have always enjoyed a reputation for graciousness and hospitality.

Stay away from the Kipper Paté — it looks, smells, and (one guesses) tastes like cat food.

Nothing about this restaurant is as remarkable as its reputation.

He has been dead for seventeen years, yet his ghost haunts my prose like the specter of Antoine Careme over a chocolate sculpture.

Acid-tongued, razor-sharp, narrow-eyed wit defined his prose. A curmudgeon through and through, his reviews are works of art unto themselves, untethered from the prosaic, dismissive of something so pedestrian as evaluating a sauce or a piece of fish. For him a restaurant was a holistic experience — an encounter he dissected from the front door to the petit fours. Calling him acerbic is like calling water wet.

New York restaurateur Drew Nieporent once described him as a Larry David-type writer, seeing things in a restaurant no one else saw. And he did so with precision and barely a wasted word. True, some of his sentences were longer than Tolstoy but, as food writer Regina Schrambling put it:

“What he did was so pared down. You got such a rich sense of the place in so few words. These days I’ll read a review, and I’m just reading and reading and reading and, oh, my god, I’m just trudging through this. You don’t have to tell us about every forkful, and you don’t pull back enough to give us a sense of a place.”

I think about him whenever I read some sad attempt to describe a dish by a too-eager amateur (and quite a few professionals) of what I call the “I liked how the flavors of cardamon and tarragon played off the crunchy spaghetti bathed in vindaloo foam” school of food over-writing.

When Seymour said “they get good produce here” you believed him, there was no need to detail the tomatoes.

Part of the needlessly flowery descriptions that have plagued food writing for the past decade can be laid squarely at the feet of chefs — to whom writers ceded the high ground of food nomenclature when they let them get away with logorrheic elucidations like:

Carpaccio of Maldivian long line caught yellow fin tuna’ – fanning an island of Rio Grande Valley avocado creme fraiche, topped with young coconut, with a splash of Goan lime, coriander and sprinkled with toasted sesame seeds

Chefs love to pad their menus with fancy descriptions like these (so they can charge more), and invariably, food writers rise to the bait and think they have to follow suit. (Mix. That. Metaphor!) Do we need to know the limes are Goan, the line was long, and the coconut young? Only if you require reminding that the fish were once swimming.

What we are left in the 21st Century is the overwrought and the under-baked. Flowery, meaningless prose, or spoon-fed pablum in pictures, videos, and Tik Toks — infantilizing our tastes as they numb our brains.

What made Seymour so entertaining was he had humor and a point of view. Good luck finding either in food writing these days.

Food writing has gotten so boring (and political) it is no surprise that videos and influencers have stepped in to fill the void. True, a picture is worth a thousand words, and our societal attention span now rivals that of a housefly, but in the end, internet influencing is just another marketing wolf aimed at those in sheeple’s clothing.

Instagram does not inform or compare. There is no depth; there is no substance. The only point of view is that of the camera’s. Thus, in less than a decade, has food journalism been reduced to a visual — no imagination needed — a two-dimensional enticement requiring nothing more than a blank stare. To paraphrase Frank Lloyd Wright: restaurant writing has devolved into chewing gum for the eyes.

If you’re in a charitable mood, you might say our communications about food have come full circle. People have always eaten with their eyes, and forever have trusted others to tell them what was tasty. It was only in the latter half of the 20th Century, when the printed word was king, economies were booming, and photojournalism was in its infancy, that paragraphs were used to convey what used to be done with a grunt.

Britchky may not have been everyone’s cup of mead, but he made you think. And he put you right there, in the place where he had sat, and let you know what to expect and whether it was worth your hard-earned cash. His only filters were his own sensibilities, and that’s what made him so much fun.

He got put out to pasture in the early 90s — a relic of a time when reading about food was almost as much fun as eating it. To this day I think about him every time I sit down to chronicle any meal I’ve had, and to my dying day I will appreciate this:

Mamma Leone’s has been called the most underrated restaurant in New York, which tells us more about the ratings than about the restaurant. There are worse restaurants in New York, but those are the ones which cannot be described in words, the ones that can only be rendered by example or anecdote. The English language can cope, however, with Mamma’s place – it is stunningly garish and ugly, the food is decent, the service automatic, the customers contented and unliberated cows with bulls and broods in tow.

…over a worthless word salad like this:

A wild array of textures—the shattering, airy crunch of meringue at the edges, and the softer one of toasted almonds, with rolling bubbles and pockets skittering across the surface. They’re more relaxed than a Florentine, more lightweight than a brittle. And they’re altogether really lovely over a cup of coffee with an old friend.

One tells you everything you need to know without mentioning a single dish; the other tells you too much and nothing at all at the same time.

As an ending tribute: a poem about him written after his death by an admiring young woman who was once his neighbor. It captures the essence of Mr. Irascible more than my words of praise ever could. Like me, Bolt is a fan. Unlike me, her view of Britchky’s world is refracted through the prism of New York reality, as well as a gimlet gaze.

Appetite of a Dead Connoisseur

by Julie Bolt

Memory:

When I was nine I rang Seymour Britchky’s

downstairs apartment asking for

an egg. He retorted:

“Egg? Me?

Food critic for The New York Times?”

and turned brusquely, slamming the door.

I stood there stunned for minutes.

Fact:

My husband is frustrated

by my ongoing predilection for ordering

and eating out, much like Seymour Britchky;

I never have an egg.

Fact:

Seymour once wrote,

“Sardi’s most famous dish

Is its cannelloni,

Cat food wrapped in noodle

And welded to the steel ashtray

In which it was reheated under

Its glutinous pink sauce.”

Memory:

When I sold Girl Scout Cookies,

Seymour intently purchased

six boxes of Thin Mints

and fourteen Peanut Butter Patties.

I met my Girl Scout goals.

Reflection:

Beard and bowtie,

Belly bordering on the rotund.

But only bordering, since Seymour

walked, walked everywhere, swiftly.

Memory:

Seymour sneered at my friends

hanging on our Greenwich Village stoop.

With tallboys, hidden joints, and bad posture.

He seethed to my mother: they are thugs.

Embarrassed, she tried to shoo them away.

Did they not know we were hungry and hopeful?

Factoidal Evidence:

1) In New York Seymour was known for:

a) Literary flourish and acerbic wit

b) Pissing off chefs

c) Really, really pissing off chefs

2) In June 2004, Seymour died of pancreatic cancer at age 73.

3) Despite his constant presence on paper, in the city streets, and his name clearly placed in our building directory, Town Hall has no record of any persons in New York by the name of Seymour Britchky.

Reflections:

I’m back to my vacant childhood home

after a decade of desert, ocean, mountain, sky.

Back to the simmering souring city I love;

I expected to see Seymour weaving through streets

Sneering and smiling; greeting, rebuking

Because he is this building, this block,

All the contradictions of this place.

Memory:

Seymour beamed each time

he passed our sheltie, Skippy.

On those rare days, he greeted us:

“Flight of angels!”

Defense

Seymour’s dead and so is my youth

But oh we are both hungry, greedy, hungry

For words, brioche, provocations, trout almondine

Cruelty and soufflé aux fruits de mer,

Peanut butter patties and beauty

Angels in the form of smiling dogs

Hungry for roast squab and squabbling

Greedy for the name in print

Even when it?s a pseudonym and upon death

There?s no proof of existence, only footprints

From Mojave to Café Loup on West 13th

Where I just passed, and Seymour Britchky,

or whatever his name was, often drank alone.

———————————-

Postscript:

Oh Seymour, could you ever have guessed, as you were hunched over your Olivetti, pecking out some lacerating putdown forty years ago, that an aging food writer in Las Vegas, in 2021, would be penning his own homage to your words? I like to think you would be slightly flattered, but from what I’ve read of you, I doubt these adorations would raise even a smile. There were no awards for Seymour Britchky. No television appearances, national recognition, public feuds or fawning fans. All you got was a poem — a poem that I like to think would’ve amused you. Only two chefs showed up to your funeral. Something tells me that would have amused you, too.

The Things At Which I Have Failed

Mom wanted me to be piano player. Got me lessons and everything. Failed miserably. (No talent/no coordination was a big issue.) Not having any of her children take to the piano (something she has loved and played her entire life – Chopin, Grieg, Mendelssohn, etc.) probably broke my mom’s heart a little bit. I’m sorry, Mom, but I sucked at piano. Wouldn’t have been any good if my life had depended on it.

Guitar, in my day, was something every 14 year old wanted to learn — the Beatles and all that — but I flamed out there as well (that pesky no talent thing again).

Then it was acting. Caught the acting bug big time in high school. Appeared in a few plays, auditioned, memorized lines, the works. Took the infection with me to college and quickly insinuated myself into the theatre department. Good looks and a big voice couldn’t compensate for other insecurities (and the nagging feeling I was destined to be the fifth most talented actor in any cast), so dreams of a career on stage were quickly dashed.

Before there was piano, guitar, and acting, though, there was baseball.

Baseball broke my heart. Big time. I loved baseball with an unbridled joy that only a little boy can have. Poured over box scores like an Ebbets Field bleacher bum. Bought book (books!?) on how to play, throw, hit, and run the bases. Played Little League insofar as I could throw the ball over the plate with reasonable consistency and once struck out Nelson Burchfield and Grady Cooksey (the Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris of Floridian fifth-graders) in the same inning. (That I can still remember this tells you something.)

I’ve never been a guy’s guy, but the closest I ever got was probably springtime in the early 1960s on a weedy, shitty, sand-spur-plagued ball field field in Central Florida shagging fly balls with a bunch of smelly ten-year olds pretending to be Willie Mays, or, in my case, Roberto Clemente.

But I was terrible at it — small, slow, stiff, afraid of ground balls and barely better on fly ones. Turned out that throwing was the only thing I could do.

Disappointing, right? But you grow up and get over it. Compared to marriage, my failings at baseball look like I went 1-for-4 against Sandy Koufax.

With baseball, at least I got in the game; with marriage, I always had one foot out the door. That is, until recently. At this point in my life I am too old to have one foot out the door. Sucking at marriage is a young man’s game. At this point, I am too old to suck at marriage.

I failed French three times in school. Tried to learn it three more over as many decades. I’m awful at French even though I love the country, the people, the wine and the food. Thankfully, the French have caught up to my sucking at their language and now many of them speak English. Thank you, French.

I tried out for the swimming team in Ninth Grade. They made me the manager so I wouldn’t get in the water.

Didn’t you hear? I was supposed to be a big television star on the Travel Channel eight years ago. That’s okay, no one else did either.

To excel at drug addiction, you have to practice, practice, practice. Drugs are great (after all, they make you feel better right now), but you have to fully commit.

I tried (mostly after my various marriages imploded), but I kept wimping out. Monday morning would roll around after some lost weekend and there I would be: brushing my teeth, shaving and choosing a necktie — a real pansy-ass who didn’t have the right stuff. Ruining your life is a full-time job — shoulder-to-the wheel-stuff and all that — and as with baseball, French, and music, I didn’t have what it takes.

But at least I gave it my best shot.

I’m not ashamed of being a failed lawyer: in fact, I’m pretty proud of it. The law is bullshit codified. Arcana for arcana’s sake in service of a racket — a racket, BTW I was knee-deep in for 33 years.

I got into law thinking it was a noble profession. Four decades later I see it as a system manipulated by the privileged few, far removed from the lofty profession seductively portrayed to me by Benjamin Cardozo and Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Had I remained a criminal lawyer (where I cut my teeth for ten years), I might not have such a jaundiced view. But instead I entered the realm of civil law (thinking it was an upgrade), where you spend your days in the service of one group of rich assholes trying to take advantage of another group of rich anal fissures. As a result, you become a money-obsessed hemorrhoid yourself. Good times.

That’s what I am today: a failed asshole lawyer….because I was never devoted enough to become the worst person I could be.

Finally, there’s politics — something I dipped my toe into after being shown the door by one of those civil law firms I misfit into. My foray was brief (only a five-month campaign for judge), but instructive. You learn a lot about yourself and your community when you run for any office, but mostly you learn how to be polite to idiots. This is a lesson I quickly forgot the second I lost the election.

The inspiration for writing this came from a documentary I was watching the other night, of all things, the Go-Go’s. (Go-Go figure.)

In speaking about the ups and downs of being a rock star, Jane Wiedlin said she took absolutely nothing from all her successes, but the lessons she did learn, and the person she is today, came about because of her failures.

Failure sucks, but it makes you tough. Picking yourself off the mat so many times teaches one thing: how to get up.

Defeat teaches you tolerance, resilience, and compassion. Victory teaches you nothing. No lessons were ever learned from a cheering crowd. The getting of wisdom does not come from exaltation, but from the struggles (internal and communal) we all endure…just like Scott Fitzgerald said.

In the end, that is all life is: an endurance contest. A game we are destined to lose, no matter how many youthful victories we have.

Once you’ve felt the sting of humiliation — from childish avocations to mature failings of character — an insult hurled your way means nothing. Scar tissue is a fine shield from the vicissitudes of fate and a certain perverse pride comes from having it in abundance.

Who would the person be typing these words if he actually had developed his theatrical chops? How different would he be if he could prattle on en Français, and had been talented at anything?

The best answer is: He wouldn’t be typing these words, and he would be a far cry from the person who functions in the world these days and lives inside my head — far more boring with a hide far less thick.

Failure isn’t the opposite of success, the saying goes, it is part of success. I had the wrong stuff, and still, here I am, taking mighty cuts at curve-balls and looking forward to my next at bat — a failure at being a failure, because I never let myself think that I was.

(Where we ate in 1958)

(Where we ate in 1958)

(With LT in Gay Paree)

(With LT in Gay Paree)

(Canocce – Mantis shrimp)

(Canocce – Mantis shrimp)

(Keep drinking and carry on)

(Keep drinking and carry on)