(Restaurant Guy Savoy, Paris)

(Restaurant Guy Savoy, Paris)Of course, the “best” of anything is a conceit and highly subjective. Measuring a “winner” or “the best” of anything — from wine to women — is a nice parlor game, but ultimately a waste of time unless there’s a stopwatch involved.

Whoever wins these accolades usually comes down to who got fawned over the most in a few influential publications — not who objectively gives diners the best food, drink, and experience. Anyone who thinks the several hundred voters who weigh in on these awards have actually eaten at the places they vote for as “the best restaurant in the world” (as opposed to forming their opinions based upon reading accounts of the few who have), has rocks in their head.

“Awards” of this sort are simply a way to give a deceptively false measuring stick to those who don’t know much about a subject. Subjectivity disguised as objectivity, all in the name of marketing to the wealthy with more money than taste. Same as with wine scores and Oscar nominations. The rich need these adjudications to convince themselves they’re doing the right thing, and “The “World’s 50 Best Restaurants” is there for them. As Hemingway puts it in “A Moveable Feast”:

The rich came led by the pilot fish. A year earlier they never would have come. There was no certainty then.

Back when El Bulli was garnering these awards (and I was voting on them), I heard from several colleagues who ate there, and what they described was more of a soul-deadening food slog (an edible marathon, if you will) than an actual pleasant experience.

A close friend (who also happens to be a chef) told me he stopped counting after 40(?) courses of (often) indecipherable eats, and was looking for the door two hours before the ordeal ended. (The trouble was, he said, there was literally no place to go — El Bulli being, literally, in the middle of nowhere.)

But Feran Adrià (like Thomas Keller before him and Grant Achatz and René Redzepi after), was anointed because, as in Hollywood, a few influential folks decided they were to be christened the au courant bucket list-of-the-moment, and woe be to anyone in the hustings to question these lordly judgments. In the cosseted world of gastronomic beneficence (and the slaves to food fashion who follow them) this would be akin to a local seamstress suggesting Anna Wintour adjust her hemline.

Because of this nonsense, we’ve been saddled with the tyranny of the tasting menu for twenty-five years (Keller, Achatz, et al), disguised foods and tasteless foams (Adria), and edible vegetation (Redzepi) designed more for ground cover than actual eating.

As far as I can tell, neither molecular cuisine nor eating tree bark and live ants has caught on in the real world — beyond trophy-hunting gastronauts, who swoon for the “next big thing” the way the fashion press promotes outlandish threads to grab attention.

Which brings us back to France. More particularly, French restaurants and what makes them so special. Let’s begin with food that looks like real food:

….not someone’s idea of playing with their food, or trying to turn it into something it isn’t. This cooking philosophy alone separates fine French cuisine from the pretenders, and gives it a confidence few restaurants in the world ever approach.

For one, there’s a naturalness to restaurants in France that comes from the French having invented the game. Unlike many who play for the “world’s best” stakes, nothing about them ever feels forced, least of all the cooking. With four-hundred years to get it right, and French restaurants display everything from the napery to the stemware with an insouciant aplomb that is the gold standard.

You don’t have to instruct the French how to run a restaurant any more than you have to teach a fish how to swim. Or at least that’s how it appears when you’re in the midst of one of these unforgettable meals, because, to repeat, they’ve been perfecting things for four hundred years. Everything from the amuse bouche to the petit fours have been carefully honed to put you at ease with with being your best self at the table.

Having been at this gig for a while, I’m perfectly aware that the death of fine French dining, and intensive care service accompanying it, has been announced about every third year for the past thirty.

I’m not buying any of it. When you go to France (be it Paris or out in the provinces), the food is just as glorified, the service rituals just as precise, and the pomp and circumstance just as beautifully choreographed as it was fifty years ago. The fact that younger diners/writers see this form of civilized dining as a hidebound, time-warp does not detract from its prominence in the country that invented it.

Whether you’re in Tokyo or Copenhagen, the style and performative aspects of big deal meals still takes their cues from the French. Only elaborate Mandarin banquets or the hyper-seasonality of a kaiseki dinner match the formality and structure of haute cuisine.

(Early man struggled with the whole pommes soufflé-thing)

(Early man struggled with the whole pommes soufflé-thing)With this in mind, we set our sights on two iconic Parisian restaurants: one, as old-fashioned as you can get, and the other a more modern take on the cuisine, by one of its most celebrated chefs. Together, they represent the apotheosis of the restaurant arts. They also signify why, no matter what some critics say, the French still rule the roost. Blessedly, there is no chance of encountering Finnish reindeer moss at either of them.

If experience is any measure of perfection, then The Tower of Money should win “best restaurant in the world” every year, because no one has been serving food this fine, for this long, in this grand a setting.

A restaurant in one form or another has been going on at this location since before the Three Musketeers were swashing their buckles. What began as an elegant inn near the wine docks of Paris in 1582 soon enough was playing host to everyone from royalty to Cardinal Richelieu. It is claimed that the use of the fork in France began in the late 1500s at an early incarnation of “The Tower of Silver”, with Henry IV adopting the utensil to keep his cuffs clean.

Apocryphal or not, what is certainly true is that Good King Hank (1553-1610) bestowed upon the La Tour its crest which still symbolizes it today:

(Canard au sang with a side of burns, coming right up)

(Canard au sang with a side of burns, coming right up)

Perfect in every respect: a twisted baguette of indelible yeastiness — perfumed with evidence of deep fermentation — the outer crunch giving way to ivory-pale, naturally sweet dough within that fought back with just the perfect amount of chew. It (and the butter) were show-stoppers in their own right, and for a brief minute, they competed with the view for our attention. We could’ve eaten four of them (and they were offered throughout the meal), but resisted temptation in light of the feast that lay ahead.

Soon thereafter, these scoops of truffle-studded foie gras appeared, deserving of another ovation:

From there on, the hits just kept on coming: a classic quenelles de brochet (good luck finding them anywhere but France these days), Then, a slim, firm rectangle of turbot in a syrupy beurre blanc, or the more elaborate sole Cardinale:

….followed by a cheese cart commensurate with this country’s reputation.

The star of the show has been, since the 1890s, the world-famous pressed duck (Caneton Challandais) — served in two courses, the first of which (below) had the deepest-colored Bèarnaise we’ve ever seen; the second helping bathed in the richest, midnight-brown, duck blood-wine blanket imaginable. Neither sauce did anything to mitigate the richness of the fowl, which is, of course, gilding the lily and the whole point.

We could go on and on about how fabulous our meal was, but our raves would only serve to make you ravenous for something you cannot have, not for the next ten months, anyway.

Yes, the bad news is the restaurant will be closing today, April 30, 2022 for almost a year — until February 2023 — for renovations. This saddens us, but not too much, since we don’t have plans to return until about that time next year. In the meantime, the entry foyer probably could use some sprucing up (since it looks like it hasn’t been touched since 1953), and we have confidence Terrail won’t monkey with the sixth floor view, or this skinny little pamphlet he keeps on hand for the casual wine drinker:

If the measure of a great restaurant is how much it makes you want to return, then La Tour D’Argent has ruled the roost for two hundred years. (Only a masochist ever left El Bulli saying to himself, “I sure can’t wait to get back here!”) Some things never go out of style and La Tour is one of them. We expect it to stay that way for another century.

À Bientôt!

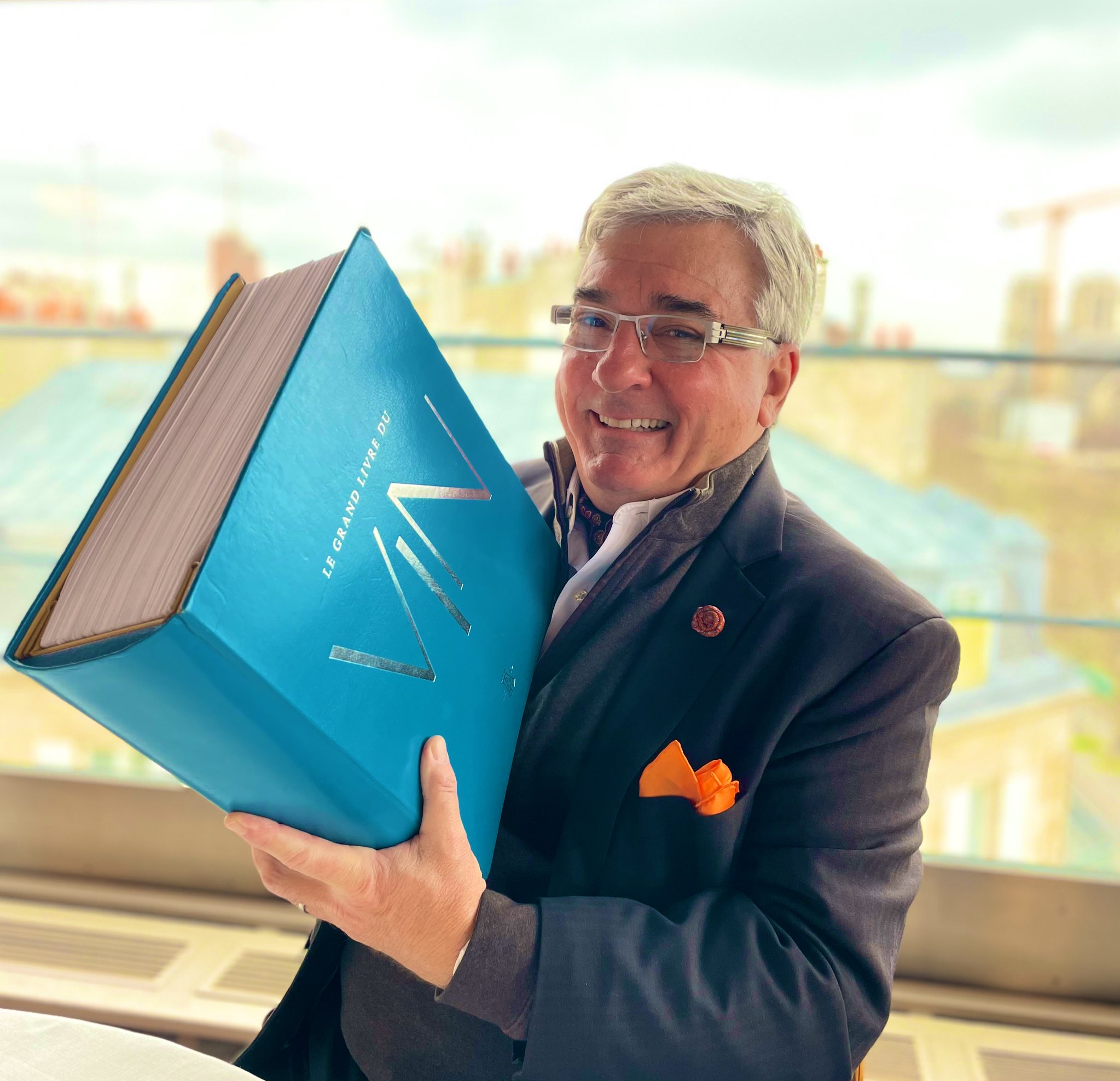

If La Tour represents the old guard of Parisian dining at its finest, then Guy Savoy — both the man and his restaurant — provides the connective tissue between haute cuisine’s past, present, and a future where new chefs will take up this mantle and teach the world what elegant dining is about.

The Adam Platts of the world may decry the “irrelevance” of the “old gourmet model”, but I stand with Steve Cuozzo in maintaining that the call for luxury and refinement in how we eat (admittedly at rarefied levels of expense), will never go completely out of fashion. Quoting our friend Alan Richman, Cuozzo writes:

As critic Alan Richman eloquently expressed it in the Robb Report a few years ago, fine dining is more than “a demonstration of wealth and privilege . . . It is an expression of culture, the most enlightened and elegant form of nourishment ever devised. Without it we will slowly regress into the dining habits of cave people, squatting before a campfire, gnawing on the haunch of a bar.”

All I can say to the Adam Platts of the world (and younger food writers who echo the same sentiments) is: If you think “the old gourmet model” is dead or dying, plan a trip to France, where formal restaurants are poised to come roaring back, indeed if they haven’t already done so.

Put another way: get your goddamned head out of that bowl of ramen or whatever Nigerian/Uzbekistani food truck you’re fond of these days and wake up and smell the Sauvignon Blanc.

Or just go to Guy Savoy.

(Savoy at his stoves)

(Savoy at his stoves)If the world’s best restaurant can’t change your mind, nothing will. Before you accuse me of bandwagon-ing, let me remind you that I’ve been singing the praises of Savoy’s cuisine since 2006, and have even gone so far as to travel between Vegas and Paris to compare his American outpost with the original. Back then (2009), the flagship got the nod, but not by much.

Since its move to the Monnaie de Paris (the old Parisian Mint) in 2015, Savoy’s cuisine and reputation have attained a new level of preeminence (which is all the more incredible when you consider he has held three Michelin stars since 1980).

With mentors like Joël Robuchon and Paul Bocuse having departed to that great stock pot in the sky, and Alain Ducasse having spread himself thinner than a sheet of mille-feuille, Savoy now rules the French gastronomic firmament as a revered elder statesman. The difference being that he and his restaurants haven’t rested on their laurels, but are every bit as harmonious with the times as they were thirty years ago. To eat at Guy Savoy overlooking the banks of the Seine from a former bank window, is to experience the best French cooking from the best French chefs performing at the top of their game. There is something both elemental and exciting about his cooking that keeps it as current as he was as the new kid on the Michelin block back in the 80s.

Dining in the dead of winter can have its challenges. Greenery is months away, so chefs go all-in on all things rooted in the soil. The good news is black truffles are in abundance; the bad news is you better like beets.

The great news is: in the hands of Savoy and his cooks, even jellied beets achieve an elegance unheard of from this usually humble taproot:

As mentioned earlier, a French chef respects an ingredient by looking at it as a blank canvas to be improved upon. Look no further than this beet hash (Truffes et oefus de caille, la terre autour) lying beneath a quail egg and a shower of tuber melanosporum, both shaved and minced:

Neither of these would I choose for my last meal on earth. Both gave me new respect for how the French can turn the prosaic into the ethereal –food transcending itself into something beautiful.

Which, of course, is what Savoy did with the lowly artichoke so many years ago, when he combined it with Parmesan cheese and black truffles and turned it into the world’s most famous soup.

There’s no escaping this soup at Guy Savoy, nor should you want to. Regardless of season, it encapsulates everything about the Savoy oeuvre: penetrating flavor from a surprisingly light dish, by turns both classic and contemporary:

We may have come for the truffles, but we stayed for the filet of veal en croute (below), once again lined with, you guessed it, more black truffles.

From there we progressed through a salad of roasted potatoes and truffles, a bouillon of truffles served like coffee in a French press, then a melted cheese fondue over a whole truffle:

…and even something that looked like a huge black truffle but which, upon being nudged with a fork, revealed itself to be a chocolate mousse. All of it served by a staff that looked like teenagers and acted like twenty-year veterans.

Suffice it to say the wine pairings were as outstanding as the food, all of it meshing into a seamless meld of appetite and pleasure — the pinnacle of epicurean bliss — high amplitude cooking where every element converges into a single gestalt.

We then went nuts with multiple desserts, including a clafoutis (above) and the petit fours carte (like we always do), and rolled away thinking we wouldn’t be eating again for two days. This being Paris, we were at it again later that night, taking down some steak frites at Willi’s Wine Bar .

>>>>>>>>>>>>><<<<<<<<<<<<<

I write these words not to convince you that Guy Savoy is the greatest restaurant in the world, or even that such a thing exists, but rather to persuade you of the transcendent gustatory experiences you can have at places like it. Until I’ve been to every restaurant in the world, I won’t be able to proclaim one of them “the best.” Even then, the best would only be what best fit my mood, my likes and my expectations at the very moment I was there.

Adam Platt was right about one thing: “the best restaurant in the world” doesn’t have to be fancy. The best restaurant in the world can be something as simple as a plat du jour of boeuf bourguignon , studded with lardons and button mushrooms in a run-down bistro smelling of wine sauces and culinary history. It can be at a tiny trattoria on the Amalfi Coast or a local diner where everyone knows your name, or that little joint where you first discovered a dish, a wine, or someone to love. But your favorite restaurant, no matter where or what it is, owes an homage to the place where it all started.

Emile Zola’s “The Belly of Paris” describes the markets of Les Halles as “…some huge central organ pumping blood into every vein of the city.” Those markets may be gone, but their soul lives on in the form of Parisian restaurants, which remain, one hundred a fifty years later, its beating heart. To eat in the great restaurants of Paris is to be inside the lifeblood of a great city, communing with something far bigger than yourself. To be in them is to be at the epicenter of the culinary universe and the evolution of human gastronomy — where the sights and smells of the food, and the way it is served, reflect the entire history of modern dining.

(Duck confit with summer vegetables)

(Duck confit with summer vegetables)

(Pan-fried Dorade with mussel tortellini and artichoke purée)

(Pan-fried Dorade with mussel tortellini and artichoke purée) (

( (aka grapes in vanilla cream sorbet in meringue crust)

(aka grapes in vanilla cream sorbet in meringue crust) (Crab “Napoleon” with lobster sauce)

(Crab “Napoleon” with lobster sauce) (Tomate stracciatella, crémeaux basilic poundré à l’olive noire – but you knew that)

(Tomate stracciatella, crémeaux basilic poundré à l’olive noire – but you knew that)