“To be a gourmet you must start early, as you must begin riding early to be a good horseman. You must live in France; your father must have been a gourmet. Nothing in life must interest you but your stomach. With hands trembling, you must approach the meal about which you have worried all day and risk dying of a stroke if it isn’t perfect.” – Ludwig Bemelmans, ‘La Bonne Table’ (1964)

“No man under forty can be dignified with the title of gourmet.” – Brillat-Savarin

“Tastes are made not born.” – Mark Twain

The plot of my life has been driven by gentle but nagging obsessions, mostly about food. Someone called me a “gourmet” recently and it took be aback. My mom and dad always called me a food snob and who was I to argue? To myself, I’ve always been a food obsessive — pondering every menu with the scrutability of a Talmudic rabbi parsing the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Some people think of food solely as fuel, but such a thought has never occurred to me. Most people think about eating when they’re hungry. By virtue of being mammals, we are compelled to eat once or twice a day, so nature basically forces these thoughts upon us. But my attitude has always been: since we have to do this thing (eat) all the time, why not make the most of it? Thus do I think about food (meals, recipes, restaurants past and future) multiple times an hour. I go to bed mentally digesting the last thing I ate, and wake up anticipating where next I will.

I’ve been thinking this way since I was 12.

But where did it all start? Was it my first taste of homemade, fresh-baked bread (slathered with apple butter) at my grandmother’s knee? The malty-sweet perfume was a revelation in freshness for a kid previously subsisting on Wonder Bread.

Or was it that first slurp of barbecue sauce? A consecrated marriage of ketchup, brown sugar and vinegar on my spoon-tender smoked pork — itself a wonder of melting meat I had never experienced — tastes so arresting I wanted to know right then and there why we didn’t eat it every day.

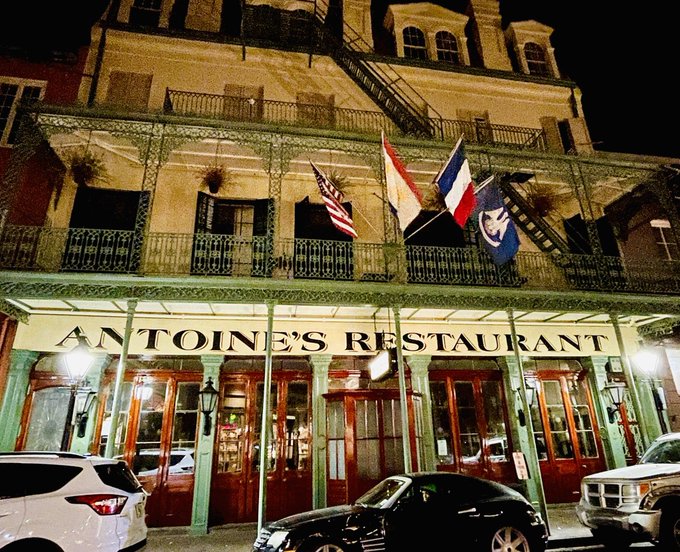

I’ve written many times before of my first trip to Antoine’s in 1964 and interrogating my mother (a classic 50’s convenience-at-all-costs cook), about why she didn’t cook this. (It was a sterling silver dish of lump Gulf crab meat, bubbling in sherry infused butter, that did the trick, in case you’ve forgotten.) Every food writer can point to a food epiphany in their youth, and those were mine.

There were multiple trips around the United States in my teens, business trips to New York, Atlanta, Miami, and Chicago with my dad — himself strictly a meat, pasta, and potatoes guy who nevertheless loved the theater of great restaurants and always took us to the best one in town.

College and law school put a crimp in my style, both for economic and social reasons: there was no currency in being a discriminating restaurant-goer back then, and the girls I was trying to bed couldn’t have been less interested in my views on fresh versus dried pasta. My first wife and I shopped and cooked the way most poor students do, while I dreamt of past feasts and future repasts.

Sometime in 1978 the bug bit hard. A divorce put me on my heels, but a steady paycheck (even at a Public Defender’s meager salary) allowed me to start cooking. A gift subscription to Bon Appétit from my big sis inspired me to use my kitchen skills to woo the fairer sex, and while I was still in my twenties, I was planning my days and weeks around what I would eat.

That women found this attractive, twenty years before anyone invented the word “foodie”, also had something to do with it.

Thus is my love of food, the way I taste and appreciate it, rooted in cooking not restaurant-going. My early restaurant epiphanies may have provided the spark, but it was working my way through magazines and cookbooks that ignited the flame which continues to burn.

These days, the word “gourmet” is seldom used, having fallen out of fashion in favor of the more egalitarian “foodie” –a word not without baggage of its own — as can be seen in the brilliant horror/satire “The Menu.” The film slices through the pretensions of modern foodie culture with the skill of sushi chef wielding a yangi-ba-bōchō: witness the scene in which the Nicolas Hoult character (a fanboy who purports to know everything about the chef and his restaurant) is asked to make some lamb chops and is exposed as a know-nothing fool.

Slavishly following chefs and regurgitating modern foodspeak is no substitute for actual knowledge, much less wisdom, as he soon discovers to his detriment. The gory plot — bathed in more blood than a boudin noir — is propelled by the über-famous chef realizing his empire is based upon catering to these idiots, and he decides to do something about it. Hilarity ensues.

Watching endless reels or videos of food (either making or eating it) cannot compete with getting your kitchen dirty and taste buds challenged. I learned to cook French before I ever mastered the art of the French restaurant (Merci: Jacques Pepin, Julia Child, and Pierre Franey), and those early years of my gastronomic education were spent more with a whisk than a wine list in hand.

At the time we were living in Connecticut, about an hour north of mid-town Manhattan and I took full advantage. This was the 80’s when Larry Forgione, Barry Wine, Rick Moonen, Brendan Walsh and others were re-calibrating America’s palate. It’s really something to have a front row seat to a revolution, and I was lucky enough to have two of them: in NYC from 1985-1990, and then in Las Vegas where I had the best seat in the house for twenty years.

Does obsessive dining out turn you into an epicure? No more than going to a lot of concerts turns you into a music expert. Ditto with home cooking: you can be a brilliant home cook but your sample size will always be too small to give you the breadth of palate you need to savor multiple cuisines in their highest form.

My argument is you have to do both: master basic techniques and then immerse yourself in how the natives and the pros due it. It also helps to have an insatiable curiosity about food, from its most pristine state to the final product. But even with all of that: cooking, reading, and restaurant obsessing….you don’t earn your stripes until you travel to where it came from.

This travel can be as simple as fishing for rainbow trout, visiting an orchard, or exploring the caves of Roquefort. Whatever it is, your learning curve is fascinating and endless, and must engender endless fascination within you if you hope to conquer the pleasures of the table at the highest level.

But here’s the rub: you will never succeed. Because for all you know, there will always be more to learn. Food and wine in whatever form, are humbling. Whatever you absorb over years of tasting, traveling, cooking, and reading will simply be scratching the surface. There’s an old Scottish saying about golf: “You don’t win the game; you just play it.” Sure, you might be better than others on some days, but until someone figures out how to get 18 holes in one, the best you can do is improve yourself, day after day. As with golf, if you think you can “win” the gourmet game, you will fail miserably. And by “fail miserably” I mean “call yourself a ‘foodie'” — someone who thinks eating out a few times a week makes them a culinary Ferdinand Magellan.

People think gastronomes, epicures, and gourmets are arrogant (think Anton Ego in “Ratatouille”), but anyone in love with a subject (as a good critic should be) is as aware of everything they don’t know about it as what they do.

At the risk of sounding like an old man yelling at a cloud, the bottom line is: you have to earn your gastronomic stripes, and you won’t succeed by scrolling social media or gastonauting your way from one chef’s table to the next. Ultimately, you should be educating yourself for yourself. Know something about everything and everything about something, is how my mom put it — which is a good mantra to chant if you decide to get serious about the world of gastronomy. But it won’t be easy if you’re doing it right, and it will take a lifetime.

So, after a lifetime of alimentary obsessions, can I claim to be a gourmet? Well, I’ve never liked the term. Its dated, inherent priggishness puts me off as much as it does someone who puts ketchup on steak.

Gastronome is my preferred descriptor, but I’ll also accept “epicure”, or even that old chestnut “food snob” — which is as accurate now as it was fifty years ago when my mom expressed both wonder and disbelief she could have raised such a creature on a diet of Wonder Bread and Mrs. Paul’s Fish Sticks.

Can I tell you the basics of a few hundred recipes in the western food canon? Sure. Do I know how things should be seasoned and when they are “done” to their best effect? Absolutely. Can I tell within minutes (sometime seconds) whether a chef is a modernist, a classicist, or phoning it in? Probably as well or better than 99.9% of people on the planet.

But can I tell upon which leg a woodcock roosted before being roasted? Or detect in which direction my sashimi was swimming in the Sea of Japan? Hardly. Can I lovingly describe the taste of samphire? Or even know what the f**k it was until I just looked it up?

Every discipline has its limits and I certainly have mine. What a lifetime in food has shown me, however, is how to train my senses to a very fine point when I am experiencing the world of food in all of its glory. Because there’s nothing more satisfying than loving something and knowing exactly why you do.