People are always asking me what do I look for in food, i.e. how do I know (or at least think) something is good, or great, or far from either.

Developing a palate for great food isn’t hard (it’s a lot easier than learning golf, or the piano), but you need two things (three, really): obsession, exposure, and experience. You can’t get anywhere trying to be a gourmet if you eat junk food, fast food, or cheap restaurant food. So, yes, there’s a fourth thing needed to do it right: money.

That’s not to say that people of modest means can’t become expert tasters, but only that, unless you get exposed to the best the world has to offer (be it in the freshest fish, the best wine, or the finest cured ham), you’ll always be playing in the shallow end. The best of anything — in life, sports, music, food, etc. — establishes a benchmark by which all others are measured. The whole point of training your taste buds is too see how things measure up.

So, let’s say you’ve been in training for a decade or so, what do you look for? (Ed. note: Anyone who thinks they can properly judge food and recipes after being a “foodie” for a few years has rocks in their head. What you like to eat has nothing to do with how good things are.)

Think of food: a meal, a dish, or a glass of wine like you would a song, a symphony, or a string quartet. Every ingredient should have a voice, but nothing should drown out the others. There should be a seamless blending of texture and flavor – whether it’s pheasant Souvaroff or a taco — and all should blend into an harmonious whole.

What you look for is balance, length and integration. Layering and complexity are important, too, but are an easy trap that too many (chefs and diners) fall into when they search (too hard) for sophistication.

The trick in tasting food and judging recipes is the rapid discernment of whether something works or does not. Just as a musician (or music critic) can quickly tell if something is out of tune, so does a food critic take a bite and tell you if the bread is a few hours too old, or the sous chef had too heavy a hand with the tarragon, or whether the vanilla-lime-picked pumpkin seed-foam brings anything to the salmon party.

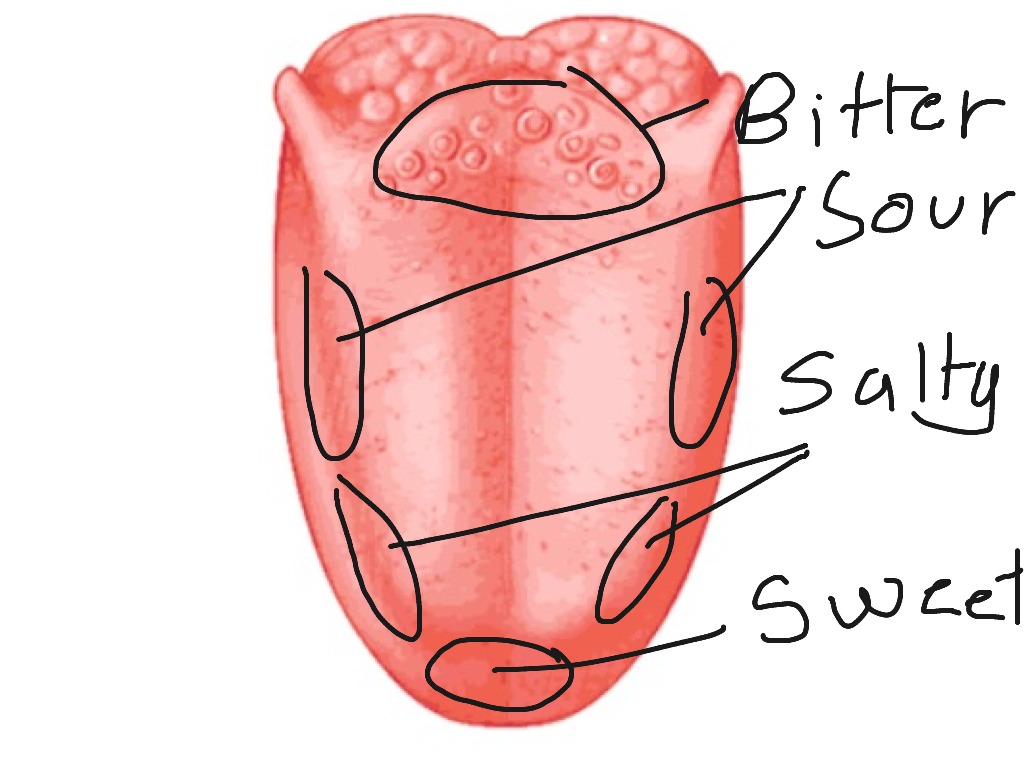

The way to start refining your palate is to start with salt and bread, and then move on to seafood. (Salt brings balance to food, and sharpness to flavors – too little and the percussion isn’t keeping the beat, too much and the lead guitar is hogging the spotlight.) As someone once said, “Salt is what makes things taste bad when it is not on them.”

Bread — warm, cold, toasted, plain, an hour or a few days old — teaches you all about texture, flavor, and ripeness in one delicious package. Different grains impart different aromas. Crusts and crumb come in a dizzying assortment of densities and crackle. Start buying different kinds of really good bread, and really thinking about what you’re tasting and smelling, and you’ll be on your way to sharpening your senses.

Seafood, like certain birds, is something of a blank canvas, which is why chefs love to play with it. But taste a lot of oysters and you start to see how the brininess of a Wellfleet differs from the sweetness of an Olympia. The dense meatiness of a Dover sole is a far cry (and two oceans away) from a bland Hawaiian escolar, and once you’ve had a wild turbot (or Copper River salmon in May), tilapia will be consigned to your trash bin. (Once you taste the real deal in salmon, the farm-raised stuff will suffer the same fate. I wouldn’t eat a piece of farm-raised salmon if it was being served to me on a naked Hedy Lamarr, circa 1938.) You may never acuity of some Japanese epicures — who, it is said, can detect whether certain fish were caught on their northern v. southern migration around the Sea of Japan — but if you pay attention to every morsel, the subtle distinctions start coming into focus.

Knowing degrees of doneness cannot be overemphasized. If professional chefs have a blind spot(s) it’s their inability to judge when something is seasoned properly (too much salt and too little everything else) and, due to the intensity of their work, recognizing when something has been fired too long, or needs a few more minutes on the flame. (They also screw up potatoes and various vegetables. All. The. Time.) Restaurant cooking is not conducive to the proper treatment of vegetables, and most chefs, privately, will admit this. Chefs are masters of organization and speed, but too often, in the heat of battle, their senses can leave them. And just as artists are the worst judges of their own (and other’s) work, so too are chefs not always the best evaluators of what is on the plate.

A successful dish gets everything right: temperature, seasonings, strong primary flavors complimented by subtle but necessary accents. You know that drum fill or vocal bridge in your favorite song (or the ascendant chorus in Ode to Joy)? The music wouldn’t be the same without them. It is the recognition of how these pieces fit, within seconds of the first time you taste them, that is the razor’s edge of the trained palate.